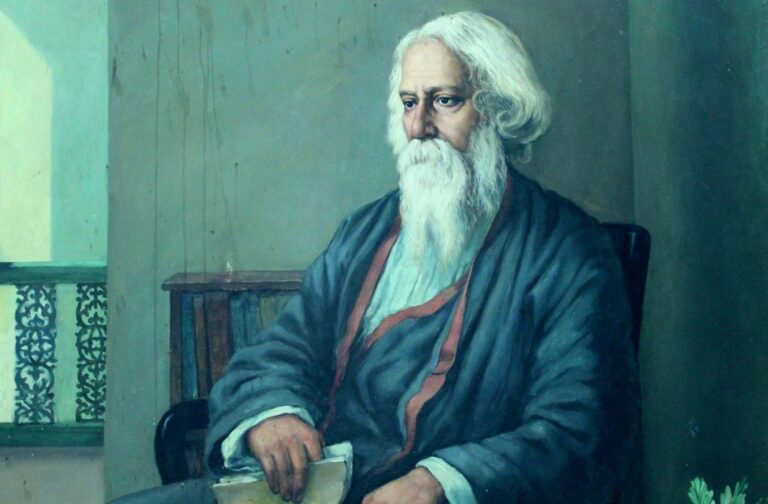

Writer as a researcher goes to Telangana State Library to unearth the Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore and his tips to Americans.

The pigeons chased each other from one chandelier to the next like expert trapeze artists, watching over the readers beneath them, at the Telangana State Central Library in Afzalgunj, Hyderabad.

Established in 1891, the library was shifted to its present location by the river Musi in 1936. My doctoral project on Indian English periodicals from the British Raj took me from one end of the city to the other, as I stood before the towering arch at the entrance of the library.

Polite enquiries in English and Hindi with the Telugu-speaking librarian and her assistants failed to make headway (they gave up when they realized that I was looking for books from the 19th century, rolling their eyes in disbelief and resignation as soon as they heard the 1800s).

Deciding to take advantage of the bureaucratic apathy, I made my way through narrow corridors and rickety wooden staircases (waking up the dogs who were sleeping beside bookshelves) to a hall, which, a board announced, was “the old periodicals section.”

Dusty graveyard of books

A second round of enquiries proved more fruitful: the library staff there (who, thankfully, spoke Hyderabadi, that charming language unique to the city) agreed to search for whatever little they thought they might have, in the form of old periodicals. We climbed a narrow wooden ladder and emerged out of a square opening onto the roof of the building — right under the scorching Hyderabad sun in an unusually hot April.

On the roof was a room which looked small from outside, but opened into it seemed like innumerable metal shelves full of books, magazines, and periodicals or what remained of them.

We were in a cavernous hall where thousands of books had been dumped and forgotten — most with their bindings completely destroyed, with pages strewn all over the floor.

One wonders how many years of darkness these piles of books had seen, for the only things which covered the entire room — each shelf and every inch of the floor– were pages covered by a thick coat of dust.

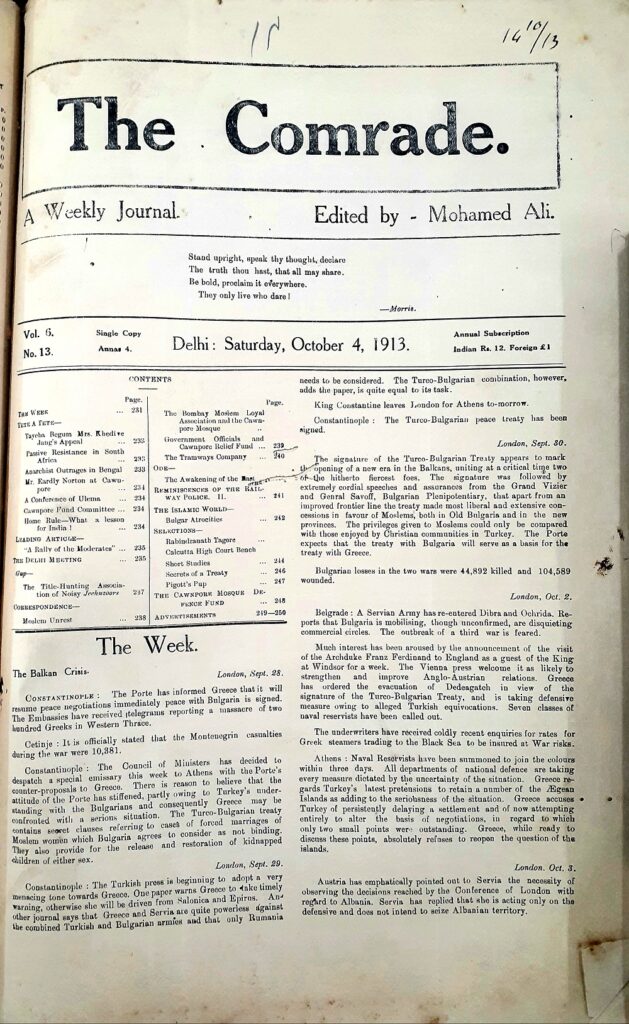

Moving through bundles of the Time magazine, the National Geographic, and the Gazette of India, I finally discovered two volumes from the first half of the twentieth century (decades beyond the period of my research, but discoveries nonetheless): The Comrade from 1913, and Gandhi’s Harijan from 1946-47, edited by Pyarelal, Gandhi’s private secretary.

The Comrade was a short-lived weekly periodical edited by Mohamed Ali (1878-1931), and published first from Calcutta and later from Delhi, before being proscribed by the British government.

Maulana Mohamed Ali Jauhar was an Oxford-educated politician, journalist, and writer, who was the leader of the Khilafat Movement in support of the Ottoman Empire in the 1920s, and a delegate at the Round Table Conference in London in 1930.

The Comrade in arms

On October 4, 1913, The Comrade carried an interview with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), who had just returned from a tour of America and Britain, where he had visited universities and delivered lectures, and had mingled with British and American literary circles. By then, he was already being hailed as “India’s great national poet”

In the interview, Rabindranath Tagore complains of “how little the English people know of India”, and that “it seems an anomaly that India should occupy such a tiny and insignificant space” in London newspapers.

The interview is particularly fascinating for the account it gives of Tagore’s observations on the British and the American public.

On his American lecture tours, he comments that “the Americans have an inordinate appetite for lectures, and I was forced into lecturing especially in the universities”.

This is reminiscent of the American lecture tours of Charles Dickens (1812-1870), half a century before Rabindranath Tagore, where the Victorian novelist was received with great fanfare, elevating him to the status of a literary celebrity.

The year 1913 is crucial in Tagore’s rise to international fame, as it culminated in the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he won for Gitanjali (a collection of poems with a foreword by William Butler Yeats, an Irish poet and a leading figure in the English literary canon) — becoming the first Indian to do so (and the second person born in India, after Rudyard Kipling in 1907).

On the difference between the Americans and the British, the poet observes:

The American is much more curious than the Englishman. In the States my Indian dress attracted embarrassing attention, and in New York great crowds followed me everywhere. That is curious, because it is a cosmopolitan city, and the people are accustomed to the sight of Turks, Arabs and Scythians. . . . On the other hand, the people scarcely noticed me in London, and I could walk through the crowded streets in my turban and Indian dress without attracting any attention.

‘I grew to like London’

Rabindranath Tagore’s experience in America echoes that of another Indian who had attracted global attention exactly two decades ago, at the Parliament of Religions in 1893 — Swami Vivekananda.

When asked how he liked London, the poet replies:

It grows on you. I had been to England twice before. On my recent visit everything was so new and strange. At first I thought it dismal: it was gloomy and rainy, and I was all at sea. I did not like the hotels (I have never liked hotel life), but later I got lodgings in Hampstead, and became acquainted with many nice people. Then I grew to like London.

Rabindranath Tagore’s reflections on London and Londoners are interesting because, as a subject of the British Crown, he offers a reversal of the imperial gaze. British travel accounts of India go back several centuries before Tagore, with one of the most well-known early travelogues being that of Sir Thomas Roe (1581-1644), the ambassador of King James I to the court of the Mughal emperor Jahangir.

Roe maintained a journal while he stayed in India between 1615 and 1619, which was widely read. By narrating his impressions of Britain (and America) in English, Rabindranath Tagore is not just reversing the imperial gaze, but also participating in a tradition of English travel writing by virtue of his medium of expression.

The interview in The Comrade contains fascinating, and at times hilarious accounts of his fellow passengers on Tagore’s voyage back to India. The following are two such amusing instances, where the poet encounters people of diverse social classes, who seek to befriend him for different reasons:

To be continued….