The book explores Kudiyattam as a phenomenon and the triangular relationship among the ways of doing of the performers, the ways of seeing of the audience and the space – Kuttampalams – which brings them together.

It is probably within a century of the delimitation of Kutiyattam (Koodiyattam) to the temples that the first kuttampalams came to be built. This structural incorporation of the theater space into the architectural complex of the temple must have gone hand in hand with the theatrical practice taking place inside it coming to acquire an inalienable place and significance within the corpus of traditional practices of the temple. A good reflection of this significance can be found in the established belief that the prime deity of the temple is himself/herself a silent spectator of the performance, with the stage facing the sanctum and with performances usually being scheduled at those times when the temple is closed to the devotees and there are no other ritual services going on.

This belief is further accentuated by the fact that in temples where there are no kuttampalams, such as Vennimala and Velloor, performances usually take place in the valiyampalam, the front part of the nalampalam, the surrounding cloister of the inner enclosing structure of the temple, facing the sanctum just like the kuttampalam.

Another belief that suggests the assimilation of the form into the larger belief structures of the temple society as well as the attempt to sacralize its practice is the notion that the three wicks of the stage lamp symbolize the trimurtis (the three principal deities), Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesvara (Shiva).

Ritual significance of Kuttampalam

With the incorporation into the systems of the temple, performances in the kuttampalam (also spelt as Koothambalam) also came to be vested with ritual significance. Practices such as the performative lamp being lighted from the flame of the lamp in the sanctum, the milavu being accorded the status of a Brahmin with elaborate a upanayana (initiation rites) being done when it is newly commissioned and installed in the kuttampalam and samskara (funeral rites) being conducted when it is finally decommissioned, the custom of the head priest announcing the performance and offering the Chakyar kura and pavitram (cloth and ring made of darbha grass), regular schedules being assigned to performances in the annual calendar of the temple in the form of ațiyantarakkuttu (obligatory performances), performances being offered as votive offerings (valipațukuttu) to the deity and the Chakyar having the right to go to the sanctum in his performance costume and offer prayers to the deity during valipațukuttu all came to be associated with the performances.

Further still, there also developed the fixed association of certain plays with certain temples, with some temples having only certain plays being performed and some others according certain plays more importance.

In such instances, there were/are clear strictures regarding what plays should be played and when, with some plays/acts being considered essential in some temples. For example, Balacaritam was a requisite for 9 days every year at the Thirumuzhikkulam temple, Anguliyankam for 12 days at the Kutalmanikyam temple at Irinjalakuda and Mantrankam at the Perumanam temple. In some other temples, such as Vennimala and Velloor, both in Kottayam district, a series of different days’ performances belonging to different plays/acts were performed in a particular sequence each year.

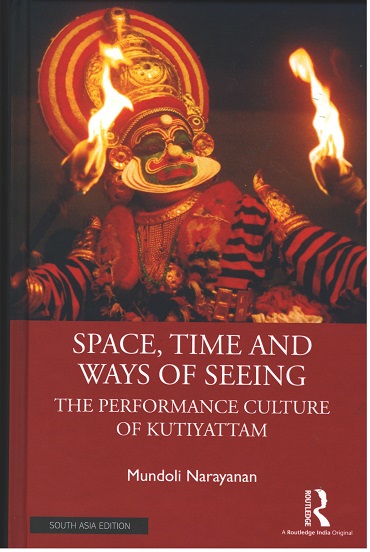

Space, Time and Ways of SeeingThe Performance Culture

of Kutiyattam By Mundoli Narayanan;

Routledge India; 300 pages; Rs 1,495

Publishing date: 24 August 2021

In some other cases, performances also came to be closely interwoven into the belief systems associated with the temples. For instance, for performances at the Perumanam temple, a member of the Musat community should sit on the stage on a special stone or pedestal from start to end, without which the performance could not commence.

The belief behind this custom is that in the olden days the presiding deity himself used to come and witness the performance, sitting on the stone, and that in one instance when he had to leave he asked a member of the Musat community to sit there and hold his seat until he returned.

The legend goes that to date the Lord has not returned and the Musat has to continue sitting there whenever there is a performance. If, in this case, the deity is considered to be (or to have been) an active member of the audience, there is also a case of an even greater embedding of the deity into the performance where he is considered a character in the performance.

At the Vennimala temple, Lakşmaņa’s role in Surpaņakhankam was never enacted because the presiding deity being Lakşmaņa it was assumed that he was a virtual presence in the performance.

As a result, in the scene where Laksmana cuts off Surpaņakha’s nose, the actor playing Surpanakha would go to the sanctum, stand in front of it and enact it by himself, followed by the scene of niņam (blood bath), right there at the heart of the temple. This practice is of importance also because it signals an extension of the performance space beyond the kuttampalam and the spilling over of performance into the general precincts of the temple, whereby the temple at large becomes the stage.