Why did the University of Chicago purchase signboard painter ‘Roja’ Muthiah’s entire collection of papers and periodicals, which was almost about to be sold to scrap?

Tamil vis-à-vis Hindi has since remained a touchy subject in the state, even though the popularity of Hindi cinema has not diminished. But, by and large, Tamil Nadu has defended its right to its language. AIR, by virtue of its having been around in the city from the 1930s, has a powerful Tamil portfolio when it comes to programming. When Doordarshan (DD) began broadcasting from the city in 1975, certain changes were made keeping in mind the sensitivity of the local populace. If Chitrahaar, the programme that featured song and dance sequences from Hindi films was telecast all over the rest of the country, DD Chennai had its Oliyum Oliyum (light and sound), which featured Tamil songs. Hindi feature films were beamed on Sunday in the rest of the country with Saturday being reserved for local language films.

In Chennai it was the other way round. As Hindi serials such as Hum Log and Buniyaad began to grow in popularity across the country, including Tamil Nadu, there had to be introductory précis by announcers on what was to follow. The mega serials such as Ramayan and Mahabharat had to be dubbed in Tamil. Those were days when attitudes hardened to such an extent that anybody speaking in Hindi would pointedly be asked to change over to

English or Tamil. And yet, people from Chennai proved adept in learning the other languages of India, Hindi included, when they had to settle in other parts of the country. That was more than what could be said of their North Indian counterparts moving South. Not that it is easy. Unlike most other languages of India, there is a clear distinction between formal, spoken Tamil and what is heard on an everyday basis. The latter is easy to master, but the former can be quite a challenge. The AIR and DD years were marked by good, clear diction and excellent usage of the Tamil language.

The arrival of the private channels has more or less dealt a mortal blow to Tamil, for, barring the news broadcasts, what is spoken is colloquial in the extreme, faulty in pronunciation, and Tanglish at best. In many ways, it follows the Tamil of Chennai, which is pidgin, evolving over time owing to various linguistic groups settling in the city. This is not Tamil but an entirely local language known as Madras bhashai. It is to be noted here that when the political fathers changed the name of the city to Chennai, they did not want the language to be known as Chennai bhashai, for this is a dialect that nobody wants to own up to.

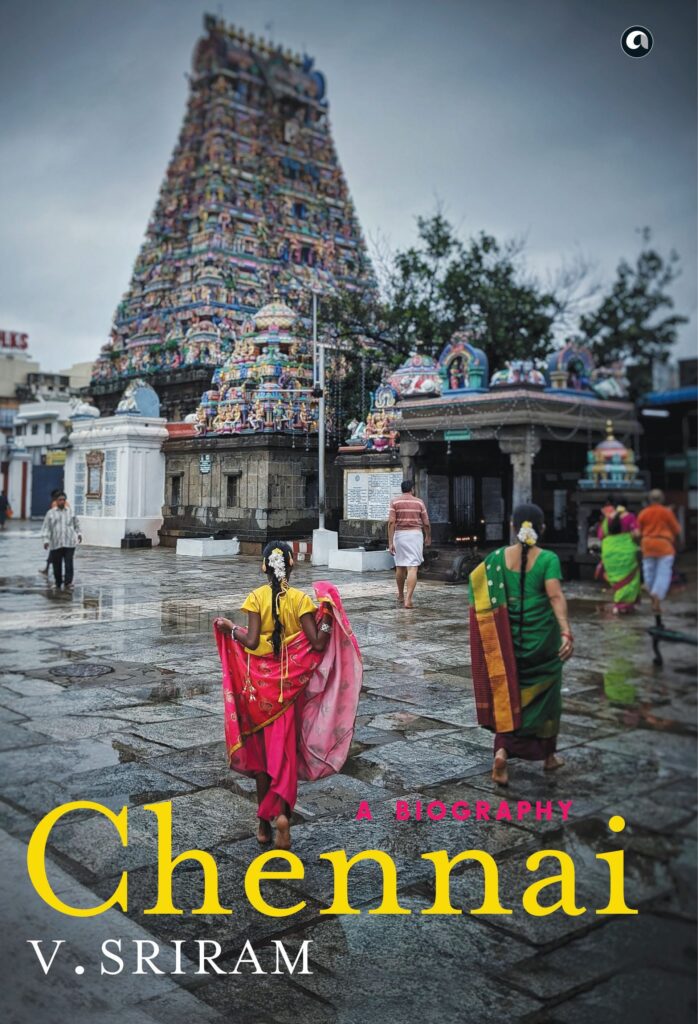

Chennai: A Biography by V. Sriram

Book details:

Chennai: A Biography

By V. Sriram

Aleph Book Company

440 pages; Rs 899

Publishing date: 5 December 2021

Imagine a base of Tamil garnished with liberal helpings from Telugu and some toppings from English, Sanskrit, and Hindi, and you get Madras bhashai. It is in many ways a work in progress, for it has evolved over time. But some gems will always remain evergreen and hopefully survive the vicissitudes of time. An offender in traffic will always be a saavu graaki (customer of death), a drunk will always be ‘full load’, and a policeman ‘mama’. Bribe is ‘mamool’, from the Telugu and Hindi term that stands for custom, showing that it has been an age-old practice in our country.

Tamil chauvinism has since had its funnier sides as well. M. Tamilkudimagan (literally means ‘son of the Tamils’), whose original name was Sathiah, became minister for Tamil language and culture in the 1996 DMK cabinet and took his portfolio rather seriously. One of his diktats was that all commercial establishments in the city had to put up signboards that featured their names in Tamil prominently.

This was taken by officialdom to greater heights when they decided to interpret his ruling to mean that all English words in names had to be translated into Tamil. There was panic in the corporate and commercial worlds as everyone scrambled to find equivalents in Tamil for English words they had used till then. To find Tamil words for ice cream, coffee, and pumps became a challenge.

In the meanwhile, bands of implementers of the ministerial diktat wandered around markets and commercial districts, imposing fines on those who had not complied, occasionally tearing down signboards. Like everything else, this too lost steam after a while and Chennai went back to its old ways.

In 2001, for reasons unknown, this Tamil champion and true scholar was denied a ticket by the DMK to contest elections, this despite the party’s love for the language. He promptly defected to the AIADMK but Jayalalithaa did not offer him a ministerial berth, which is what he had hoped for so that he could implement whatever he had left unfinished. He died in 2004.

There has been progress in the development of the Tamil language as well. Serious research into Tamil is conducted at many places across the world. Chennai too has played its part. Scholars such as Marai Malai Adigal and U Ve Swaminatha Iyer worked in this city. The University of Madras contributed as well, its Department of Tamil embarking on a lexicon in that language in 1913, completing it in 1936, with S. Vaiyapuri Pillai, R. P. Sethu Pillai, and V. Venkatarajulu Reddiyar, all hallowed names, working on it. A further 20,000 words were added by 1939. In 1954, a concise Tamil lexicon was brought out.

The International Institute for Tamil Studies came up in 1970 in the city. In 1978, the then MGR government made some modifications to the script, chiefly to rationalize certain practices. These came to be accepted only in part and that too only in Tamil Nadu, with other Tamil-speaking countries preferring to stick to tradition. In 1981, the MGR government set up what had originally been proposed in 1925—a Tamil university, located in Thanjavur.

By the 1950s, research in Tamil had spread across the globe and it was the American scholars who pointed out a treasure trove that lay right in Tamil Nadu’s midst. This was the collection of printed matter in Tamil painstakingly put together by ‘Roja’ Muthiah, a signboard painter in Kottaiyur, Chettinad. The prefix came about because he had a habit of signing all his artworks with a rose. He began his collection in 1950s and naturally acquired a lot of what was printed earlier as well. By the time of his death in 1992,

there was a 100,000-strong collection of printed matter—periodicals, books, newspapers, posters, leaflets, and wedding invites. It had been put to good use by scholars the world over and when it came to be known that Roja Muthiah’s descendants were planning to sell everything as scrap, there was consternation. The University of Chicago stepped in and purchased the entire lot and then decided that it ought to remain in Tamil Nadu. The collection was shifted to Chennai in 1994 and was housed initially in Mogappair East before shifting to the Central Polytechnic Campus in Taramani, where the government placed a building on long lease at its disposal.

The Roja Muthiah Research Library has since grown to a 300,000-strong collection but its future remains uncertain, chiefly owing to lack of funds to carry on its good work. In the meanwhile, even as it manages a hand-to-mouth existence, scholars make a beeline to it. All that professed love for Tamil has not seen the state government extend much help. And when it has offered help, the end result has often been counterproductive.

Marai Malai Adigal’s vast personal collection of books was, for years, housed in a library dedicated to his name, in North Chennai. This did not see much patronage but it was at least open to scholars. The Government offered to make it a part of the Connemara Library and when that happened the collection just became part of a large ocean, accessed with great difficulty.

Tamil has also often been used to suit political ends. The ‘threat of Hindi’ is revived each time an election is due. There are more visible markers as well. On 1 January 2000, then chief minister Karunanidhi unveiled a 133-foot statue of Thiruvalluvar at Kanyakumari, thereby setting off a race of sorts to erect giant statues all across the country by various political parties. In 2010, he decided to host yet another World Tamil Conference on the lines of what his mentor had done in 1968. The state government was increasingly in the news for the wrong reasons—corruption, nepotism, and its equivocation over the Sri Lankan government’s final push in its battle against the LTTE.

The IATR, however, refused to grant its stamp of approval but the DMK went ahead, hosting what it labelled the World Classical Tamil Conference in Coimbatore and converting it into a political broadcast in every way. The voters unfortunately were not impressed. But it did result in plenty of civic improvements in Coimbatore.

In 2016, the Edappadi Palaniswami-led AIADMK government decided to score some brownie points by getting the Tamil diaspora to crowdsource a Tamil Chair at Harvard University. It was pointed out by critics that the money could have been put to better use by improving facilities for research in Tamil in one of Tamil Nadu’s many universities.

(Excerpted with permission from Aleph Book Company from the book Chennai: A Biography)

Write to us at [email protected]