Nangiarkoothu would have joined the list of extinct traditional art forms of Kerala if not for the efforts of this curious dancer.

Mohiniyattam is not just a dance form. The art involves intense research into the postures, music and bring in a harmony among the existing styles and schools of Mohiniyattam. The decades of research I put into Mohiniyattam also helped me grow as a teacher. In the previous article, we learnt about the formulation of a system of training in Mohiniyattam at Natanakairali, a dance research training centre founded by G. Venu in 1975, to encourage the growth and progress of traditional dance art forms.

The viralis lead the way

We also discussed my inclination to highlight the potential of acting tradition into Mohiniyattam. My intention was to systematically analyze the dance and bring back the concept of acting into Mohiniyattam. The description of the body movements and emotions expressed through dance by viralis or the female dancers of the Sangam period is proof enough that lasya was the foundation of their dance technique. In the chapter on Arannettam in Chilappatikaram, the epic tale of Kovalan and Kannaki’s pious love for Kovalan, the word ‘viṟali’ is thus defined: ‘Viral ennal satwamavatu’; and the explanation is given as:

“Ullattu nikalum kurippunikkerapata

Utambinkan nikalum verupatu”

Itu viral enavum pedum (This is also called viral)

This expressional dance also proves that enough that artistry and virtuosity were present in equal measure in the dances of viralis. In some of the commentaries, the dance of the virali is compared to that of a peacock dance. This also implies that her style of dance is characteristic of lasya dance style consisting of delicate and graceful dance movements. Several forms of classical dances such as Mohiniyattam, Bharatanatyam Odissi among others have evolved on the bases of Lasya style of dance.

Another interesting fact emerges from these descriptions – that the dance style of these dancers was not only a blend of pure lasya form but also incorporated an advanced form of acting.

Focus on Nangiarkutthu

We now know that the enriched style of Mohiniyattam resembles the lasya technique to a great extent. As mentioned earlier, my intention was to bring back the blend of time-honoured art and acting – especially the facial expressions – into Mohiniyattam, which was lost in the passage of time. For this purpose, I decided to concentrate on Nangiarkoothu (or Nangiarkuttu).

In Kerala’s female dance traditions, the facial acting (mukhabhinayam) of Nangiarkoothu is considered one of the oldest surviving art forms. However, since this also had suffered neglect, not many knew of this art form at the time of my ongoing research. The Nangiars or the Nangiarammas who practised the tradition of Nangiarkoothu gradually lost touch with their core art form and established themselves as actresses. References of these could be found in the oral as well as written traditions of Nangiarkuttu.

To my disappointment, no matter how much I tried, I wasn’t able to watch a Nangiarkuttu performance. This was because little was known about this art form. Moreover, I could not gather any information worth mentioning since Nangiarkuttu’s condition was worse than that of Mohiniyattam during its phase before the revival.

The research continues…

Kodungallur, the birthplace of Chilappatikaram was also conducive to many research attempts and performances of dramatics. The Kodungallur kings or the Kulasekharas encouraged female dance traditions of Kerala. Their encouragement and support extended from the 7th century A.D. to the second half of the 19th century. The efforts made by Balarama Varma who wrote Balaramabharatam and Swathi Thirunal Maharaja of Travancore for the revival of these female dance forms of Kerala have been acknowledged in this series.

I have also extensively discussed this feature of ‘abhinaya’ in dance with Ammannur Madhava Chakyar, who had learned acting in the Kaḷari of the Kodungallur kings. Considering the Kodungallur kings and their quest to encourage the female dance traditions of Kerala, I presume that their experiments in the field of acting must have been greatly influenced by the female traditions of acting then prevalent in Kerala. Moreover, it is also mentioned in Balaramabharatam that it was written after observing the lasya dance style of the danseuses. The fact that Ammannur asan trained in acting in the Kalari of the Kodungallur acted as an impetus to choose Ammannur asan as my Guru in acting.

However, when I enquired about Nangiarkoothu, he suggested that it would be better to approach the Nangiars who are the real practitioners of the art. During this discussion, he mentioned Subhadra Nangiaramma and Kunjukuttipilla Kutty Nangiaramma; and was generous enough to offer help whenever I needed.

Baby steps all over again

In those days, Nangiarkoothu was not being taught anywhere in the region. This is how it worked: to earn the title of a Nangiar, a girl from the Nambiar family had to learn Nangiarkoothu and perform the ‘Aragettam’ in the temple.

Since it was a ritualistic performance, only the rudiments of Nangiarkoothu, just a few slokas and related acting were taught to these girls. And for this purpose a portion of Srikrishna Charitam Nangiarkoothu was taught to every girl child.

I approached several Nangiarammas such as Kochukutty Nangiaramma who was in Kottayam; later, when I settled at Irinjalakuda, I met Kunjipalla Kutty Nangiaramma, Subhadra Nangiaramma and Sita Nangiaramma. I also visited some of the prominent Nambiar Madhoms such as Chattakutam and Kalakattu. But they also taught their girls what little was essential for ritualistic performance – say, the first 15 slokas, and were not interested in the entirety of Nangiarkuttu as an art form.

With Kunjipillakutty Nangiyaramma

Light at the end of the tunnel

Truth was, those who were familiar with that were far gone into old age. Srikrishna Charitam Nangiarkuttu was practised exclusively by the Nangiar community. Disheartened, I approached Ammannur asan again.

Luckily, Gopinathan Nambiar from the Onakkoor (Piravom) Nambiar Madhom, had brought an acting manual of Nangiarkoothu and presented it to Venu.

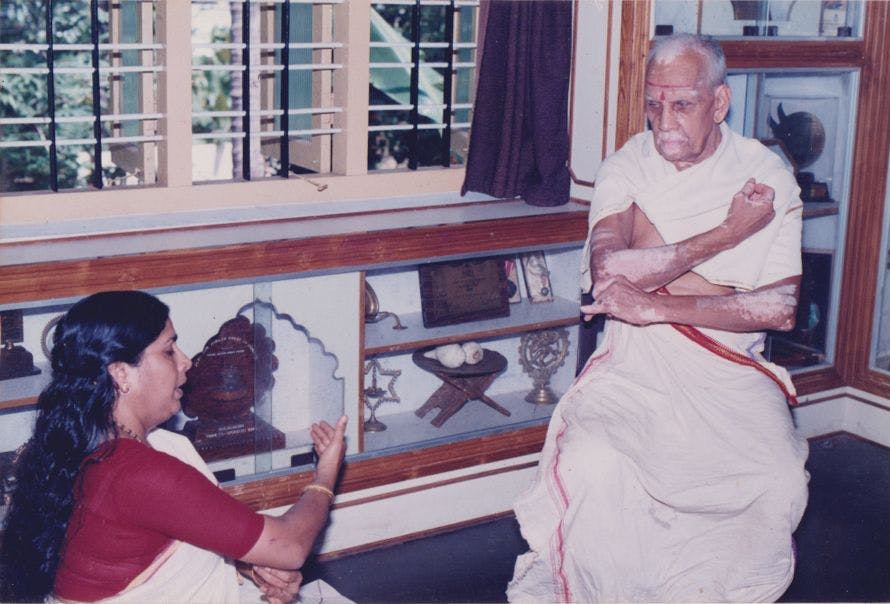

With Guru Ammannur

This is how Guru Ammannur started teaching me the slokas, mudras and facial acting based on this. We found time in the afternoons to learn the mudras, once Guru had completed his lunch and siesta. Ammannur Parameswara Chakyar, Madhava Chakyar’s older brother, whom we respectfully address ‘Vaidyarettan’, gave his full support for the endeavour.

Whenever I visited Kerala during the summer vacations from Ooty, he taught me the shlokas from the Srikrishna Charitam Nangiarkuttu. When confronted with unfamiliar mudras, Kootiayattam asan often sent me to Kunjipillakutty Nangiaramma or Subhadra Nangiaramma for clarity.

This is how I became the first student of Nangiarkuttu, which was being revived at Irinjalakuda. I consider this the greatest blessing of my life.

(Assisted by Sreekanth Janardhanan)

Click here for more on the series