Reports of rising violence among youngsters—ranging from school bullying and street brawls to extreme acts of aggression—have become disturbingly frequent. Does popular media, particularly cinema, play a crucial role in shaping this growing culture of aggression?

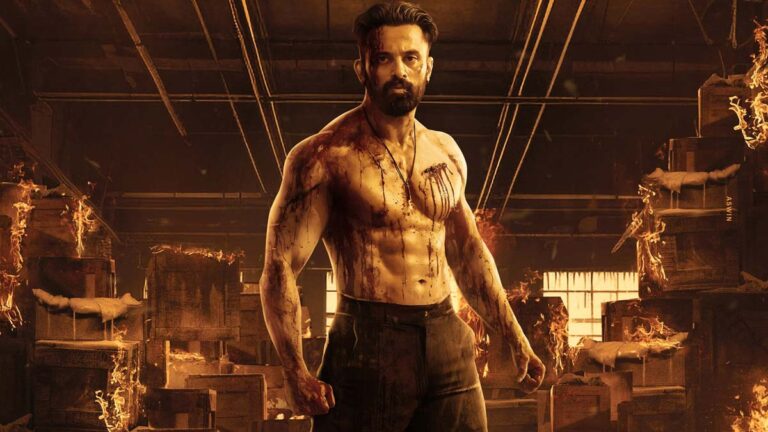

Marco, the recently released Malayalam film directed by Haneef Adeni and starring Unni Mukundan, deliberately disregards conventional norms regarding on-screen violence. While popular culture often fails to capture the full extent of real-world trauma and brutality, censorship has traditionally regulated violence in visual media. Marco, however, abandons such constraints, presenting extreme violence without restraint.

The phrase “art for art’s sake” once encapsulated a significant literary movement that upheld art as an entity independent of moral or ethical imperatives, valuing aesthetic coherence and structure above all. The debate over whether art should remain true to its form, detached from its socio-political context, continues. Yet, are not all texts, particularly in the space of art, shaped by social anxieties, ambivalences, and underlying tensions? In this sense, texts and their contexts exist in an intersemiotic relationship—a continuous, evolving interplay of affect and meaning.

But when we watch Marco, we question its language of violence which lacks any aesthetic sensibility or decorum for the film to exist as a complete text on its own even if we ignore the contextual significance an art piece may carry.

Violence in cinema

In cinema, violence is typically justified by narrative necessity, often serving as a critical plot device that drives character development, underscores thematic concerns, or provides catharsis. For instance, in The Godfather (1972), violence is integral to the transformation of Michael Corleone from a reluctant outsider to a ruthless mafia leader, illustrating the inescapable cycle of power and retribution.

Similarly, Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012) employs stylised violence to expose the brutality of slavery while empowering the protagonist’s quest for justice. Even in Malayalam cinema, Kammattipaadam (2016) portrays violence as an unavoidable consequence of systemic caste oppression, giving it a socio-political dimension.

Malayalam films such as Stop Violence (originally titled Violence but later changed due to censor board criticism, 2002), Bachelor Party (2012), Visudhan (2013), Kala (2021), Nalla Nilavulla Rathri (2023), and Pani (2024) are some examples of cinematic portrayals of violence. However, each of these films is anchored in a compelling narrative that conveys a deeper contextual meaning to the audience. In other words, the depiction of violence is framed within a strong ethical structure that shapes the storytelling.

But, Marco employs a cliched revenge plot—a protagonist avenging the death of a loved one/s—hardly an extraordinary theme in Malayalam cinema or global storytelling. Yet, what sets this film apart is its lack of any moral framework governing its portrayal of violence. Traditionally, certain ethical considerations shape the representation of violence against women and children, but Marco disregards these entirely, dismantling all artistic codes of restraint.

The normalisation of violence

This critique does not mourn the decline of moral standards but rather examines how violence is becoming normalised in popular media, ultimately influencing real-life behaviour, as critic T.T. Sreekumar argues. Despite Kerala’s progressive reputation, the state has seen a rise in violent crimes, including arson, stabbings, and murders linked to black magic. Recent incidents of ragging, political assassinations, hate crimes, honour killings, and brutal murders further highlight the erosion of ethical boundaries in society.

When the censor board granted an A certificate to the film, it was streamed uncut on the OTT platform, challenging the very notion of censorship, as public viewing practices have significantly evolved with the rise of digital streaming. These platforms have, in fact, democratised access to content, allowing unrestricted viewing for a diverse audience. In this context, the very act of streaming Marco on an OTT platform contributes to the normalization of violence. Furthermore, the memes that emerged following its OTT release employed humour to downplay the film’s violent graphic content, reinforcing a process of naturalization that ultimately encourages public engagement with it.

Greed serves as the catalyst for the film’s relentless violence, pushing visual storytelling to disturbing extremes. No one—infants, children, the elderly, women, or even animals—is spared from the killing spree, underscoring the film’s unflinching portrayal of human depravity. The opening sequence, depicting a gladiatorial combat cheered on by a bloodthirsty crowd, sets the tone for a narrative saturated with brutality, where violence is not just an act but a spectacle.

Even moments meant to depict camaraderie, love, and familial bonds remain overshadowed by Marco’s menacing presence, as if violence itself has become an inescapable force governing human interactions. The film’s aesthetic choices—tight framing, rapid cuts, and an unsettling soundscape—intensify the atmosphere of dread, making the audience complicit in the horror they witness. In doing so, the narrative critiques the cyclical nature of violence, questioning whether love for the family is merely an excuse for barbarity.

The spectacle of gore

While many films offer little intellectual depth but provide some aesthetic pleasure, Marco reduces itself to a mere choreography of mutilation and slaughter, devoid of any aesthetic/ entertainment value. Violence was always part of art and literature texts including the ones that are hailed as classics. However, they had served the purpose of catharsis in different ways.

For example, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, while ending in carnage, derives its cathartic power from its exploration of human flaws and tragic inevitability. There are several films that evoke pity and fear while portraying grotesque visuals. Marco, by contrast, elicits not pity or terror but sheer revulsion, as its disclaimer subtly acknowledges. One particularly egregious scene involves the violent coercion of a woman in labour, followed by the brutal handling of her newborn—an act devoid of any artistic or narrative justification. If such films thrive at the box office, it is crucial to examine the consumerism that fuels their success.

Marketing violence

The film’s commercial triumph suggests an audience increasingly desensitized to violence, conditioned by an “eye for an eye” mentality that normalizes brutality as both entertainment and retribution. Unlike Rifle Club (2024), where violence remained within tolerable limits and carried moral weight, Marco offers no such justification. Instead, it indulges in gratuitous gore, catering to a niche audience drawn to visceral brutality, reinforcing the idea that extreme violence is not just acceptable but desirable in mainstream cinema.

This shift signals the growing marketisation of violence, where bloodshed is no longer a narrative device but a commodity in itself. Filmmakers, recognising this lucrative appeal, may now exploit the trend by escalating on-screen savagery to even more grotesque levels, pushing ethical boundaries to maximize shock value and commercial success. In essence, Marco does not merely depict violence—it embodies it. Violence is not just its language; it is its very essence, packaged and sold to an audience who are now conditioned for ever-intensifying spectacles of gore and destruction.

1 Comment

It’s such a relevant topic, especially with how graphic and intense modern films can get—sometimes it feels like violence is being used just to shock the audience rather than say something meaningful.

What I really liked about the piece is how it doesn’t take a black-and-white stance. It acknowledges that violence can be a powerful storytelling tool, especially when it reflects real human struggles or serves a deeper purpose in the plot. Think of classics like Schindler’s List or Parasite—the violence there isn’t just for show; it’s emotionally heavy and meaningful.

But then, of course, there’s the other side—films that go overboard just to grab attention or boost box office numbers. The article calls out that trend without being preachy, which I appreciated.