Author and researcher Shashank Shekhar Sinha explains how a Sufi saint influenced the choice of Fatehpur Sikri, the new Mughal capital under Akbar’s rule.

The shift of the Mughal capital to Fatehpur Sikri seems on the surface to be a sudden decision. However, investigation into the context tells us that there was more than one reason for the building of the new capital. Mughal association with Sikri had begun during the time of Babur. During the Battle of Khanwa (1527) against Rana Sangram Singh of Mewar, Babur had stationed himself on the banks of the lake in Sikri. He is said to have renamed the village as Shukri, indicating ‘A Place of Thanksgiving’, in recognition of the support he received from the inhabitants during the battle. Babur also started the construction of a garden at Sikri and named it Bagh-i Fath or ‘The Garden of Victory’. Some historians say it was probably the name of this garden which later inspired his grandson Akbar to rename the area as Fathpur or Fathabad. Sikri had played an important role in the development of Agra as well. When Akbar ordered the re-building of the fort in Agra, the construction material came from the quarries of Sikri. Contemporary sources inform us that around 1,000 cart loads of sang-i surkh or red sandstone were brought from Sikri every day. The quarrymen employed by Akbar are said to have constructed a small mosque near the khanqah (hospice) of Shaikh Salim Chishti, now known as the Masjid-i Sangtarash or the ‘Stone-cutter’s mosque’. This mosque is especially noted for its serpentine struts or brackets supporting chajjas or stone projections from the top of the building to protect it from the sun and rains – an architectural device also employed in later Mughal buildings.

Shaikh Salim Chishti’s influence is known to have played an important role in the building of the new capital in Sikri. Akbar’s first meeting with Shaikh Salim Chishti took place in 1568. Akbar wanted a son and requested the saint to pray for him. Later, the emperor was so overwhelmed with the saint’s grace that he sent the pregnant Rajput queen Mariam Zamani to Sikri, where she was initially lodged in the Chishti quarters. Akbar ordered the construction a ‘lofty palace’, identified as Rang Mahal now, for the queen. The next year, a son was born to Akbar and named Salim, who later became known as Jahangir, in honour of the saint. A grateful father now decided to lavish on Sikri the resources of a vast empire.

When Sikri was being built, the emperor erected for his revered saint a white marble mausoleum in the courtyard of the congregational mosque. But Sikri meant a little more than just the presence of the Sufi saint, Salim Chishti. It represented the ‘growing need of the emerging empire to have a new capital, a town planned around a visionary, appropriate to the new vision of an empire’.

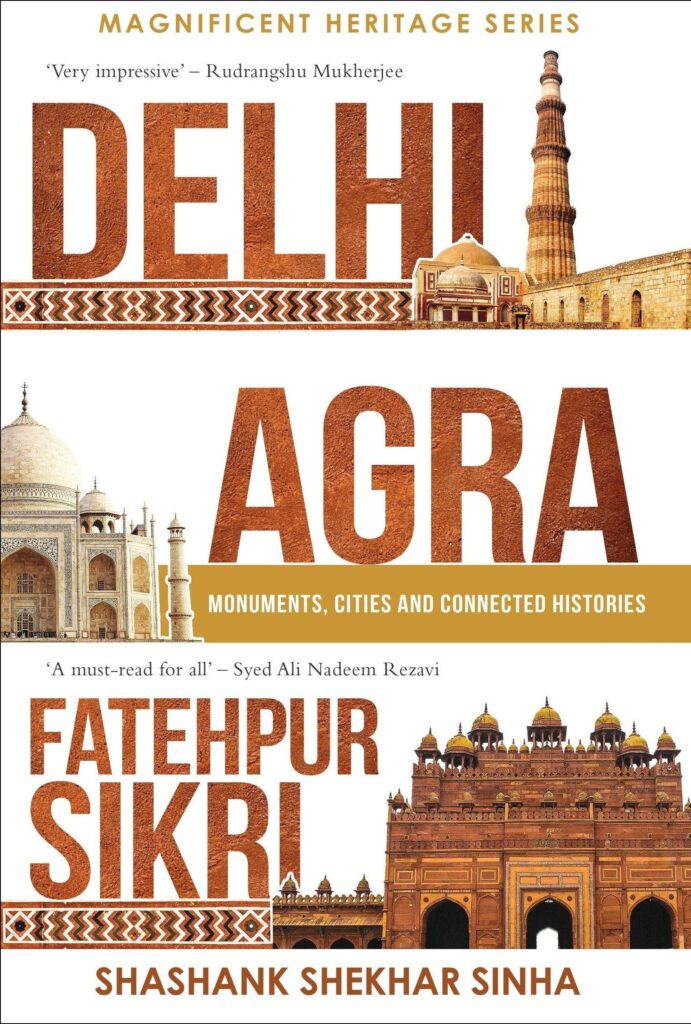

Book Details

Delhi, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri: Monuments, Cities and Connected Histories

Author: Shashank Shekhar Sinha

Publisher: Pan Macmillan

Pages: 416

Price: Rs 423

Publishing Date: 23 September 2021

Sikri as a city was different from Agra; the latter was known for its impregnable palace-fort and a strong political and military establishment. Agra had strong gates and security arrangements in place and many political campaigns were launched from here – it was more about political domination. Sikri was the next stage in the evolution of the empire as it tried to strike deeper socio-cultural roots with focus on integration. The monuments at Sikri also exemplify how the emperor was trying to integrate a population with very diverse socio-religious inclinations, address conflicts within the conservative Islamic clergy and also enhance the spiritual position of the emperor. Scholars say Akbar was exceptionally innovative in designing and building his new court and administrative city – it was an embodiment of his own changing policies and widening religious beliefs. So while some structures within the imperial complex – such as Diwan-i Aam or ‘Hall of Public Audience’, Diwan-i Khas or ‘Hall of Distinguished/Private Audience’, harem, hammam (bath), karkhana (manufacturing centre under state supervision) etc – served the same purpose as their Agra Fort counterparts, others like Ibadat Khana (‘House of Worship’) served a different purpose.

Sikri bears testimony to Akbar’s incorporation of Rajputs in the nobility and marriage alliances with them; his adoption of Hindu and regional architecture; his distancing from the orthodox Sunni traditions and ulema; his dabbling with other religious heads including Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Christians, and Zoroastrians in the Ibadat Khana; his veering towards Christianity under the influence of visiting Portuguese Jesuits; his proclamation of the famous mahzarnama (1579) which made the emperor the ultimate authority in all matters involving interpretations of the Quran and Hadith; and the development of a new court culture centring around the ‘universal sovereign’ – where the service to the emperor paved the way for highest virtue and spiritual- religious merit.55 The new capital also saw Akbar promulgating the policy of sulh-i kul, variously interpreted as ‘universal peace’, or ‘tolerance for all’.

The incorporation of Rajputs manifested prominently in the aesthetics of Fatehpur Sikri: adoption of their ideas of rulership seen in the institution of jharokha – a balcony from where the emperor presented himself seated to both the public and private audiences; presence of many Rajput women in the imperial household; and permission to Hindu chieftains to access innermost parts of Akbar’s palace, a privilege even denied to the Muslim courtiers.

But Sikri was also about some big conquests for the empire. In 1572–73, Akbar led an expedition to Gujarat. Like its eastern counterpart Bengal, Gujarat was a region of agricultural wealth, hand-made manufacturing and flourishing overseas trade. The Arabian Sea had served as a base for the Portuguese, Ottoman and Indian ships. Upon return, Akbar built the famous Buland Darwaza or ‘the Lofty gate’ in the congregational mosque complex to commemorate his victory over Gujarat. Sikri now also came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri or the ‘City of Victory’.

In 1585, Akbar suddenly left Fatehpur Sikri for Lahore, never to come back to the city again. When he returned, he based himself in Agra. The immediate motive behind this move was the death of his brother Mirza Hakim (d. 1585) who had somehow been able to control the Uzbeg and Safavid invasions. Akbar’s positioning at Lahore enabled him to secure the strategic Punjab area and the surrounding regions including Kabul, Lower Sindh, Kashmir and Qandahar and also facilitate commerce. The years 1598–1601 saw Akbar embroiled in warfare in the Deccan primarily against Ahmadnagar and Khandesh. When he returned to Agra again in 1601, he was faced with his son Salim’s revolt which threw the empire into instability and factional fights for almost five years. Thanks to the peace brokered by the ladies of the harem, Salim and Akbar reconciled before the latter’s death in October 1605.

(Excerpted with permission from Pan Macmillan from the book Delhi Agra Fatehpur Sikri: Monuments, Cities and Connected Histories)

Write to us at editor@indiaartreview.com