Madhava Chakyar might have been a world-renowned performer, but he maintained an austere lifestyle through the years in his home town at Irinjalakuda, visiting the temple early in the morning religiously, clad in just a mundu. But such was his devotion to Koodiyattam that he would discourage disciples from learning or even watching other art forms

Madhava Chakyar accepted all invitations for public events without any reservations. But he never maintained a calendar of events.

One day, Chakyar came over, looking worried. Someone had invited him for a meeting somewhere. But he had completely forgotten who and where even the date! Thinking hard, he said, “I remember that someone like you (he meant a writer like me) was also supposed to attend that meeting. I asked him if it was the noted author Kunjunni Master. ‘Yes’, exclaimed Chakyar. Immediately, I rang Kunjunni Master. Funnily enough, Master had also forgotten all about the meeting!. In short, no one had any idea of the meeting. Again, I told him not to worry. “The organisers will come for you on the appointed day. If no one turns up, don’t bother!” Chakyar went back. I don’t know if the meeting ever took place. But I watched Madhava Chakyar transform from being a staunch traditionalist to someone who was not averse to attending public meetings and making speeches.

Devoted son

Chakyar was devoted to his mother. The word devoted would be an understatement. For him, his mother was everything. He could not bear to see his mother in tears. I remember an incident that Chakyar had told me. One morning, before breakfast he had a small tiff with his mother and left home without having his coffee. When he returned later in the day, he found that his mother had not eaten all day. When he asked her why his mother broke into tears. ‘If you don’t want to drink the coffee I made for you, why should I cook or eat anything? Why should I keep a cow if not to get fresh milk for you?’ she asked. Remorse filled him and never again did he refuse anything prepared by his mother. Even as Chakyar was telling me this story, his eyes brimmed with tears.

This devotion to his mother extended to another being also, his cow. As mentioned by his mother, she had started rearing the cow for fresh milk, for her only son. And for the son, the animal deserved equal devotion. Whenever he was away from home, he worried if the cow was being properly looked after.

Chakyar was blissfully unaware of many of the contemporary cultural figures. Once, he was invited to present the Muttathu Varkey Memorial Literary Award to Malayalam writer Anand. As Anand hails from Irinjalakuda, the organisers decided to conduct the award ceremony here. I was also invited to attend the function. However, on talking to him, we realised that Chakyar had absolutely no idea about Anand or Muttathu Varkey. But it hardly bothered him.

As far as he was concerned, all that mattered in the world was Koodiyattam. His devotion to the art form was so complete that he never watched any other art form. His disciples were also not encouraged to learn, or even watch other artforms, as he feared it would contaminate the purity of their practice. Whether the younger generation followed, was a different matter. But he never wavered from that path. Also, he did attend that award ceremony, presented Anand with the award and gave a brilliant speech, despite not knowing who Anand was.

Death of Bali

One of Madhava Chakyar’s famed performances was the death of Bali, the monkey king of Kishkindha, in the play ‘Balivadham’. He used to emulate the last breaths of a dying being exactly, much to the awe of the spectators. As he got older, doctors warned him not to perform the act in such a realistic manner, as they were afraid that it’d actually affect his lungs. Chakyar had once told me that he had mastered this act by observing his own mother’s last moments.

Madhava Chakyar continued his temple routine well into his old age, till he was bed-ridden. I was much younger than Chakyar, but as I was plagued by illnesses throughout my life I used to take great care of myself. I would always put on monkey caps and woollen sweaters during cold mornings, as I stepped out to open the gate of our house at the break of dawn. Chakyar would be walking to the temple, fresh from his bath in the pond, clad only in a wet mundu, with his thorthu (bathing towel) thrown over his shoulders. He would smile cheekily at my woollen cap and sweater and ask, “Is it that cold?” I’d smile back, and take the taunt from a great master as a blessing. Who would believe that this man, walking to the temple in a single mundu and a towel, was one of the most respected performers of the world?

Koppilil Radhakrishnan (Dr K Radhakrishnan, the former Director of ISRO) once told me that he was stunned when he suddenly came face to face with a huge portrait of Madhava Chakyar at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris! He felt proud to belong to the same town as the thespian.

I too have often felt that it is truly a blessing to be a contemporary and friend of such a great person as Madhava Chakyar. It is a pity that Madhava Chakyar has no proper memorial in our town. When our Municipal Town Hall was being built, many of us felt that it should be named after Madhava Chakyar. But it was named after Rajiv Gandhi, instead. Recently, I heard that there is a proposal to open a centre of the Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady, at Irinjalakuda, an initiative of our Minister for Higher Education, R Bindu. I sincerely wish there would be a Chair in the name of Ammannur Madhava Chakyar in the Centre to encourage research on his contributions as well as on Koodiyattam.

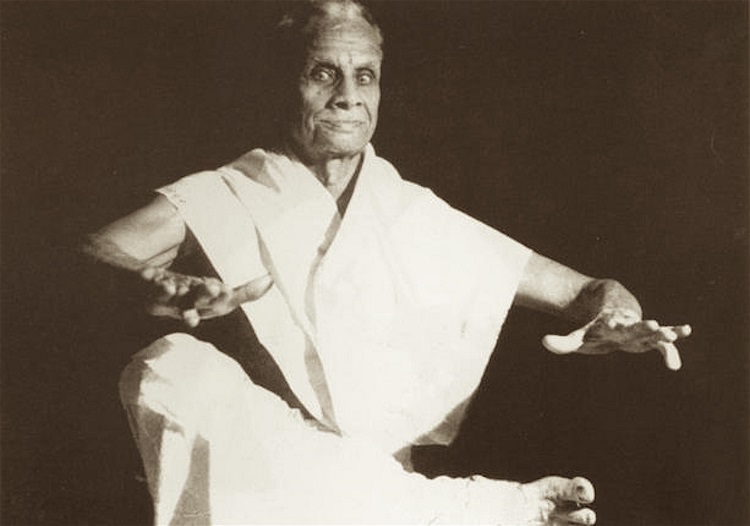

Cover image: Bali on Angada’s (his son’s) lap. Bali – Ammannur Madhava Chakyar, Angada – Pothiyil Narayana Chakyar and Sugreeva – Ammanur Kuttan Chakyar. Photo by: Camilla Van Zuylen, Holland(1987).

Read Part one

1 Comment

Kudos for capturing the subtle naunces of the personality of a legendary torchbearer of Natyasastra. Proud to hail from his neibhourhood and to grow watching his masterly performances at the ‘Koothambalam ‘ of Sree Koodalmanikyam temple during my childhood and to watch his portrait at UNESCO, Paris during my engagements there during 2001-2005.