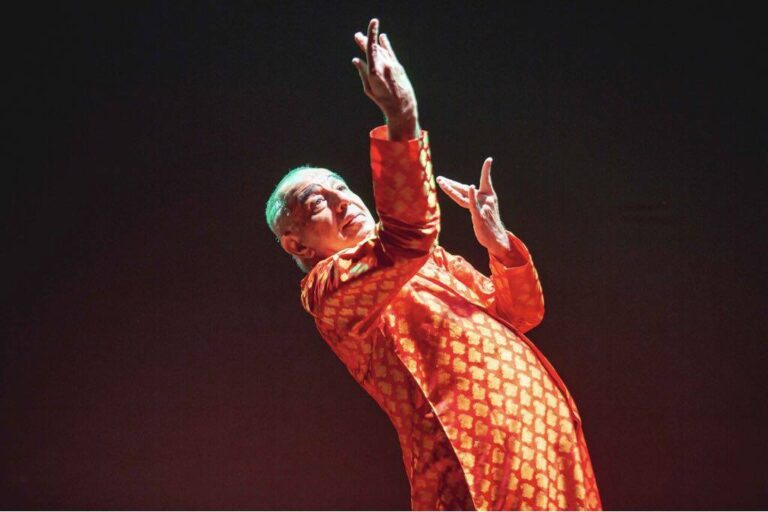

Astad Deboo blended Kathakali with Kathak which gave him a stamp, but the contemporary dancer had no bounds when it came to experimental choreography.

As a teenage student of contemporary dance, I first came upon Astad Deboo three decades ago. Not on stage, but as a fairly established name in the field. That was in 1989 when I was taking classes under renowned choreographer Narendra Sharma in Delhi.

On the weekends, Sharma-ji’s Bhoomika School held video sessions featuring dancers. The idea was to give us youngsters exposure to masters the world over. One such session had Bombay-based Deboo-ji on the screen. I was impressed beyond words. More so with two elements: slow balancing and body control.

Deboo-ji’s physical language came across as completely new. What’s more, he performed solos mostly. It’s really tough to hold the audience for an hour or more as the lone performer. Classical dancers do it in India, but not their contemporary counterparts.

Soon, in 1990, Bhoomika inducted me into its dance group. In a couple of years, I saw Deboo perform. At Kamani Auditorium, opposite Doordarshan’s headquarters in Delhi. That time, the maestro was dressed in a bodysuit. It was in complete contrast to a loose costume he subsequently made his signature.

At Uday Shankar fest

In 1993, we in Bhoomika were in Calcutta for a cultural festival. In memory of iconic dancer Uday Shankar, also the guru of Sharma. Deboo-ji was there too. Ah, with a bigger surprise! He danced with a life-size puppet, which Dadi Pudumjee donned in the collaborative venture. The concept, its execution and the style stunned me.

In 1995, I left Bhoomika to do independent work. By then, Deboo-ji had become a stalwart in Indian contemporary dance. He was a regular at all major festivals around the globe.

Shortly, Deboo-ji performed at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi. Again, a novelty. It was in sync with an installation work by celebrated artist MF Husain. I remember the white fabric and black chairs. The visual treats inspired me like none other. I was in awe of Deboo-ji’s keenness to explore art, realising there is no limit to ways of choreography.

Then came my first opportunity to interact personally with Deboo-ji. That was at an art show in Triveni Kala Sangam along the famed Mandi House circle. He was watching the exhibits and I went and introduced myself. He was very warm, and it turned out to be a fairly long chat.

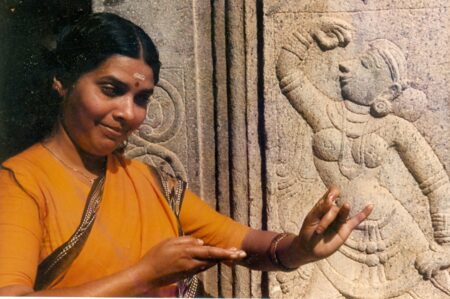

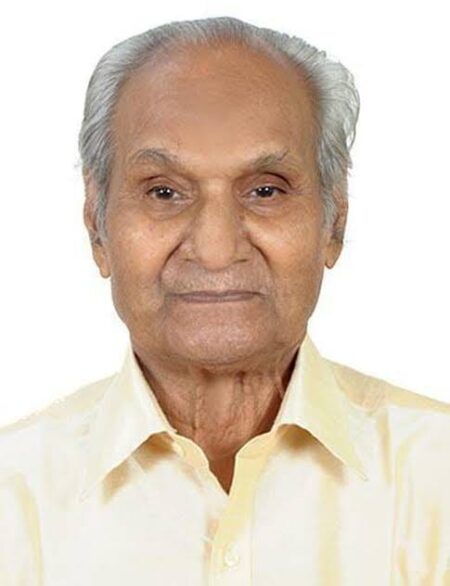

I realised he knew my father Kalamandalam Padmanabhan, a Kathakali dancer. The Kerala dance-drama was something Deboo-ji too had learned as a youngster from E Krishna Panikar in down-state Thiruvalla in 1977. I too had studied Kathakali and would occasionally perform too. Overall, the commonality brought us closer.

In 1998, I founded Sadhya. Months later, we worked with filmmaker Mira Nair’s NGO named Salaam Balak Trust. Deboo-ji went on to invite the Sadhya artistes engaged in that endeavour for the benefit of street children. We, in return, co-opted some of his students into our group. Later, in 2007, my own students, specialised in Chhau dance, got an invitation from Astad and were sent to Mumbai.

Sadhya’s esteemed guest

In 2013, when Sadhya celebrated its 15th anniversary, Deboo-ji was our guest of honour at the function in Kamani. He spoke with affection at the function and, subsequently, at the dinner we hosted at India Habitat Centre.

This year, as Covid-19 induced a nation-wide lockdown in March, we at Sadhya thought of video work with the environment as the theme. The virtual dance production had Astad among the participants. Each of them would dance for a line delivered as a voice-over. The master was initially hesitant in joining this kind of a show, but soon he overcame the technological hiccups. The work, spanning a little over five minutes, was fairly successful.

Only that I didn’t realise my first dance film involving Deboo-ji would also be the last. Today, I learned he was suffering from cancer, which was diagnosed well into the fourth stage. The death was totally unexpected, very sad.

My tributes to the great master.

As told to Sreevalsan Thiyyadi.

Santosh Nair is a Delhi-based contemporary dancer. He is the founder of Sadhya, a Unit of Performing Arts.