Devadasi tradition was a part of Kerala temples as well, shows history, though they were more respected and were even made queens, at times.

The Devadasi tradition existed in parts of South India until the beginning of the 20th century. However, there is no evidence for the prevalence of the tradition in regions that are part of present-day Kerala. This, however, does not mean that there were no temple dancers here. In ancient poetic compositions of Kerala like Sukasandesam and Chandrotsavam, there are references to Devadasi dancers. The latter poem makes it clear that Devadasis had a highly respected place in society. It is a well-known fact that Kulasekhara Perumal, the ruler of Kerala in the ninth century CE, dedicated his own daughter to the Sriramgam temple.

Devadasis were respected

The history of Kerala has many examples of beautiful women of the Devadasi sect being accepted as consorts by kings. Devadasis Kantiyur Tevitichi Unni, Cherukarakkuttatti and few others had become queens too. The chief among the queens of Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagar was Devadasi Chinna Devi. What is more, it was not uncommon for maidens from royal or Brahmin families to become Devadasis. Uttara Chandrika, the heroine of the Nanneli Kavyaṁ belonged to the Chirawa royal family. Traveller Bukkaner has recorded that even Brahmin women could be found among the Devadasis of Mysore and Kerala.

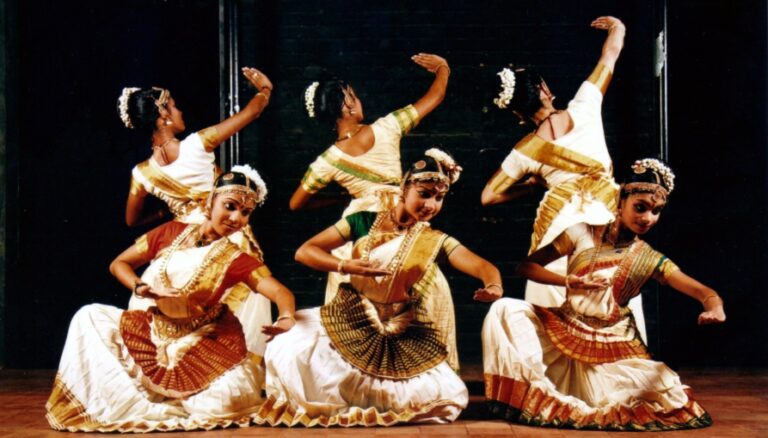

The Devadasi tradition of dance is considered the artistic representation of the eager yearning of the Jeevatma to merge into the Paramatma which is represented by the deity of the temple.

Duties of a Devadasi

The Devadasi is supposed to be the consort of the deity of the temple (deva-vadhu). So, when a maiden is received by a temple as a Devadasi, a token wedding is performed to the deity of that temple so that she becomes a deva-vadhu. This ceremony used to be performed in temples at the time of taking a maiden as Devadasi. In some of the temples of Kerala, this ceremony was called penkettu. When a maiden thus becomes a Devadasi, the temple would give her Kudi (a house to live in) and Padi (food or means of livelihood). In the famous temple of Suchindram, there were about 32 such Devadasi Kudis. And many of them came from Thrissur District.

Temple, Thrissur District, Kerala

The chief duties of Devadasis were singing and dancing, but they were often employed to do some other duties also in certain temples. For example, in the Tiruvanchikulam Temple when the deity was taken round the temple in procession at the time of Siveli or Sribali the Devadasi had to hold the Tookkuvilakku. This duty was given to members of three families and it is believed that these families were awarded the privilege by the great ruler Cheraman Perumal who brought the dancers. As the Devadasis were supposed to be the spouses of God, they would never become widows. To see a Devadasi when one sets off on a journey or business was considered to be auspicious. When a king set out for some important purpose, Devadasis were purposely posted at his door so that he might have their auspicious sight on coming out. When the Maharaja of Travancore went on a tour, the Devadasis of each village had to receive him as he entered the village and escort or accompany him in his ‘journey’ through that village.

Devadasis in the modern era

In the famous Athachamayam procession at Tripunithura, the Devadasis had a special place. This custom was in vogue till very recent times. There were Devadasis in many Kerala temples till the British prohibited the institution by law.

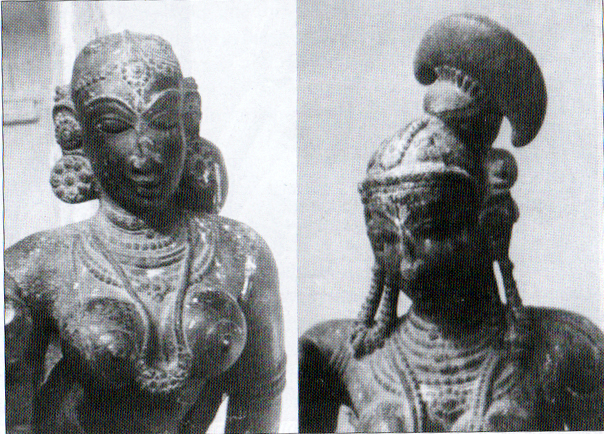

All the evidence found so far about the temple danseuses of Kerala is from the 10th century CE or later. During that period the danseuses were known by various names like Nanga, Talinanga, Nangachi, Nangayar, Nangaiyar, Talivadhu, Koothathi, Koothaachi and Tevidichi.

References in history

A stone inscription from the year 932 CE found in the Chokkur Siva Temple near Calicut contains references to the dancers of Kerala of that age. The inscription mentions how one Nangayar belonging to the Chittarayil family donated some land to the temple.

Another valuable source of information about Devadasis is a record of the year 934 CE from the Tali Siva Temple at Nedumpuram. This document mentions the payments made to Nangais (dancers) and Nattuvans (teachers of dancing). Nattuvan is the word to denote the dance Guru of a temple. So it is evident that in those days Devadasis, as well as their Gurus, were attached to Kerala temples. In an inscription from 12th century CE obtained from the Vadakkumnathan Siva Temple of Thrissur, it is recorded that there were Devadasis in that temple.

In the book Kerala Charitṛattinte Aṭisthana Rekhakaḷ author M. G. S Narayanan quotes a document, quite a noteworthy one, of the Kollam Rameswara Temple. On a palm leaf written in 1102 CE (Malayalam era 278), information is provided regarding the expenses for Tirupavaikuttu and Tirukuttu met from that year onwards. Pavaikuttụ refers to the Kuttụ (dance or theatre) performed by women and there are many such references to Pavaikuttu in old Tamil texts. There is a reference to the Pavaikuttu danced by Lakshmi Devi and it can be considered as the dance of Mohini. We can conclude that an art form called Pavaikuttu used to be performed during the 11th century, at least in some temples of Kerala.

Read Part 11

(Assisted by Sreekanth Janardhanan)