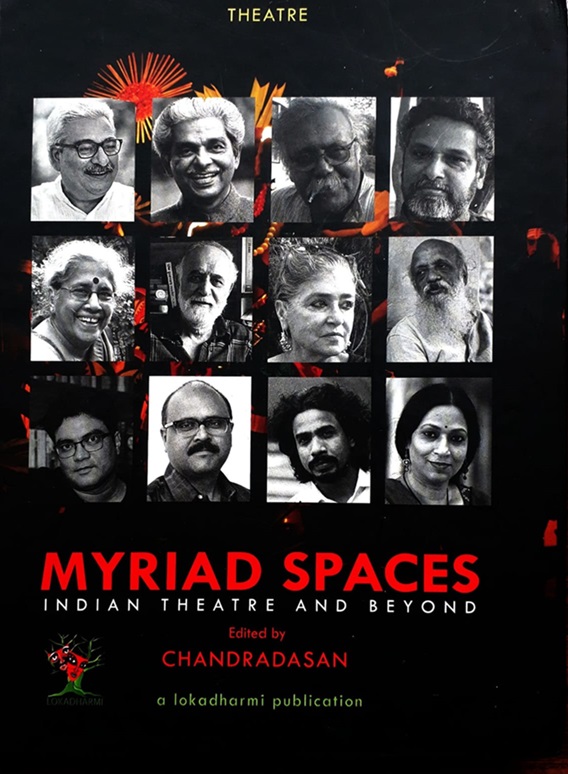

Myriad Spaces: Indian Theatre and Beyond, edited by Dr. Chandradasan, which delves into diverse aspects of theatre through insightful talks by prominent figures.

When the pandemic struck the world and paralyzed all spheres of human activities, the community of artists was the worst affected. However, strangely enough, a few among them were determined to brave the challenges, realizing the words of Shakespeare: “There is a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries.”

The Kochi-based Lokadharmi, a center for Drama, theatre training, research, and performance, working since 1991, rose to the occasion by organizing a series of talks by thespian celebrities. Theatre practitioners from across the country interacted with them, thereby bringing the arc lights on the myriad aspects of theatre in its entirety.

The book titled “Myriad Spaces; Indian Theatre and Beyond” is the product of this unique endeavor and perhaps the only one of its kind. Truly a treasure trove for posterity.

Divided into four sections, namely 1. A Reflection, 2. In Retrospect, 3. The Process, and 4. On Stage, the book is edited by Dr. Chandradasan, the founder-director of Lokadharmi. Each section carries talks by three experts, thereby bringing a total of twelve. Interestingly, each talk is followed by interactions by the participants, which are also documented.

“A Reflection” begins with the observations and suggestions by Bansi Kaul on ‘The Actor and Space”. Incidentally, the very idea of the talk series was discussed by Chandradasan with Kaul, but regrettably, he did not live long to see the book in print.

Against the backdrop of varied experiences and experimentations, Kaul argues that “The space in theatre is actor’s space”. He has connected the design of the space to his childhood memories in Kashmir and further to rural life throughout India. In this connection, the description of his interactions with traditional street artistes, wrestlers, and clowns and how it affected his design, aesthetics, content, actor training, and pedagogy is both interesting and educative.

Embracing folk traditions

Prasanna’s Indian Method in acting, the next, underscores the need for connecting with rural traditions of theatre. He argues that Indian theatre concentrates on the actor, the play, and the audience, and these three are abundant in the folk theatre all over India. “Even in a small village, two to three thousand people are willing to come and watch the play. But in the last few years, because of the confusion that arose, when we did not know whether we are Indians or foreigners, whether we are followers of Stanislavski or Brecht or others, we lost that audience”.

Russian theatre practitioner

Prasanna, also an advocate of folk tradition, exhorts contemporary actors to tell the rest of the world to come to India and learn the Indian ways of theatre, which is excellent. He has explained at length the services of Ebrahim Alkazi, Shanta Gandhi, Adya Rangacharya, B V Karanth, Badal Sarkar, and others to elaborate his affinity to rural traditions.

While talking on Indian Shakespeares, H. S. Shivaprakash digs deep into the many productions of Shakespearean plays in India. He avers that, “There are two ways of doing Shakespeare: to repeat what Shakespeare has written or to repeat what he has done. Repetition is translation and recreation is adaptation. Recreations are much better and more Shakespeare-like than translations.” And he has substantiated this through many examples.

Exploring abhinaya technique

The second section, “In Retrospect,” opens with Abhinaya in Natyasastra by Dr. K. G. Paulose. The intrinsic techniques enunciated by Bharata are explained succinctly, and the explanations chapter-wise leave nothing untouched. It is interesting to read how the Koodiyattam performer Rajaneesh Chakyar had expatiated on certain abhinaya techniques with a demonstration.

M. K. Raina too is a strong supporter of folk traditions, which he proved while narrating the travails of staging Bhand Pather, a folk play from his homeland Kashmir. This he did when terrorism posed a constant threat in the state. His topic was Kashmir and its Performance Tradition. His interactions with the folk artistes have convinced him that the strength of Asian theatre emanates from the improvisation of the action, words, music, and dance; in short, all elements of theatre.

Though commercial in nature, Parsi theatre had embraced themes that highlighted social evils like untouchability, dowry system, caste system, superstitions, etc., and had contributed immensely to our Independence struggle. Hema Singh in her talk on Parsi Theatre Revisited bemoans that this form was totally sidelined after 1950. While giving all its salient features, she believes that we need to revisit the theatre form and explore its potential.

The third section starts with a talk on Process and Production by Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry. Against the backdrop of her rich and varied experience, she speaks extensively about the text of a play. “No text can be dreamed about the same way by different directors. It will be imagined by different directors in different ways at different points in time,” she points out. She adds that once a play has been written, it has a life of its own that goes beyond the intentions of the playwright. The plays come alive differently in the mind of the director and in the body of the actor, according to her.

Though short compared to other talks, the relevance of her discussions was evident from the volley of clarifications sought by the participants.

Chandradasan’s talk on Actor, Voice, and Speech smacked of his pedagogic style – he is a retired professor of Chemistry – with lots of exercises that would enable an actor to give out the right tone to his dialogue in a play. The exercises are part of Vocology, a recent branch of the science of voice that is useful to voice-users in general. In the second part of his talk, he elaborates on the Stanislavskian and Grotowskian approach to speech, which is specific for actors. The former explains that the meaning of a word in theatre may not be the meaning in the lexicon, a view that is shared by Grotowski as well. He insists on connecting the voice of the actor with the whole body and also with the space around. Further, he lays more importance on the tonal quality of the sound.

Polish theatre director

A rarely discussed topic in theatre circles, it has been done quite elaborately by Chandradasan.

Harmony and dissonance

Subhadeep Guha is a musician conversant with all genres of music, from Baul to Western Classical, and also well-versed in all musical instruments, both primitive and modern. He talked on Theatre and Music; The Inlaid Symphonies & Cacophonies. He believes that music does not have a different identity from theatre; it is inset and inside the performance and is within the text. “You have to bring up those unheard and unsaid things from inside, from within,” he says.

As for him, if theatre has three-dimensional aspects, then music will add a fourth dimension and also a different perspective to it. Guha also narrated his experience while scoring music for various plays.

The book concludes with section four, namely On Stage. Deepan Sivaraman deals with Materiality of Space and Objects in Theatre, one of the longest. He opens with the term Katha Patra, which he explains as the vessel that, according to him, is the body of the character. If space is material, materiality is more complex. He underscores the role of scenography and explains the emergence of the designer and emphasizes the body of the actor and its relation with the space around. The position and role assigned to the spectator by way of the design of the space decide the experience of theatre. These ideas have been amplified by citing examples through plays like Dark Things, Talatum Daughter’s Opera, Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Khasakinte Ithihasam.

Kirti Jain goes further about these concepts in her discussion on Devising Theatre. She ignores the hegemony of the text and argues in favor of creating her own text, the performance text along with the performers. This is where devising begins. In devised theatre, you do not know anything except the idea which is to be developed through the processes of improvisations, experiments, and different kinds of creative strategies. This process has greater spontaneity and it allows greater collaborative work. It is more democratic and less hierarchical.

Abhilash Pillai in his talk on Post-Dramatic Theatre explains how drama and theatre got separated during the second half of the last century thanks to a host of stalwarts like Ibsen, Chekov, Strindberg, Maeterlinck, and Hoffman as they questioned the social structures and also the form of drama. Aspects of text, space, time, body, and media became analytical tools in post-dramatic theatre. Each of these parameters has been discussed with numerous plays. The plays Raj Darpan, Memories of a Legend, Manganiar Seduction, 409 Ramkinkars, Heads are Meant for Walking Into, Midnight’s Children, and Glass House Project are skillfully illustrated to highlight these aspects.

A review of the book can hardly bring out the seminal ideas given by these scholars, academicians, and acclaimed authorities of Indian theatre. Each talk has to be read and reread to digest the ideas they have put forward.

It is commendable that biographies and contributions of each of them have been given. Totally, the book is a didactic tool for the entire fraternity of theatre practitioners, especially students and researchers of the thespian art.

The services rendered by the ten-member back-up team in transcribing and also editing are praiseworthy.

Published by Lokadharmi Kochi

Price: Rs 695