It’s not just books that are filled with stories, libraries and their settings too speak volumes.

As you glance across the long table, on the wall beside the entrance, you find two large paintings staring solemnly back at you. With thick, wooden frames, they capture two iconic moments of the British conquest of India: the first is the image of a vast populace after the Battle of Seringapatam (Srirangapatna) in 1799, many with their heads bent, perhaps mourning the loss of the Sultan. The second is much more well-known: Shah Alam granting (surrendering, rather) the Diwani of Bengal to Robert Clive in 1765.

At another place, at another time, another image: this time, not a painting, but a slip of paper stuck to a book with dates stamped on it – from “Jan 29, 1914” to “Sept 27, 1924”.

A century-old date slip – that constant companion of all library books – on a volume of a periodical from the early 1900s, once housed in a library in Pennsylvania, now resting for the past few decades in a university library in Hyderabad.

The paintings are from the Salar Jung Museum Library in Hyderabad, while I encountered the date slip at the Indira Gandhi Memorial Library (IGML) at the University of Hyderabad.

Discovering hidden gems

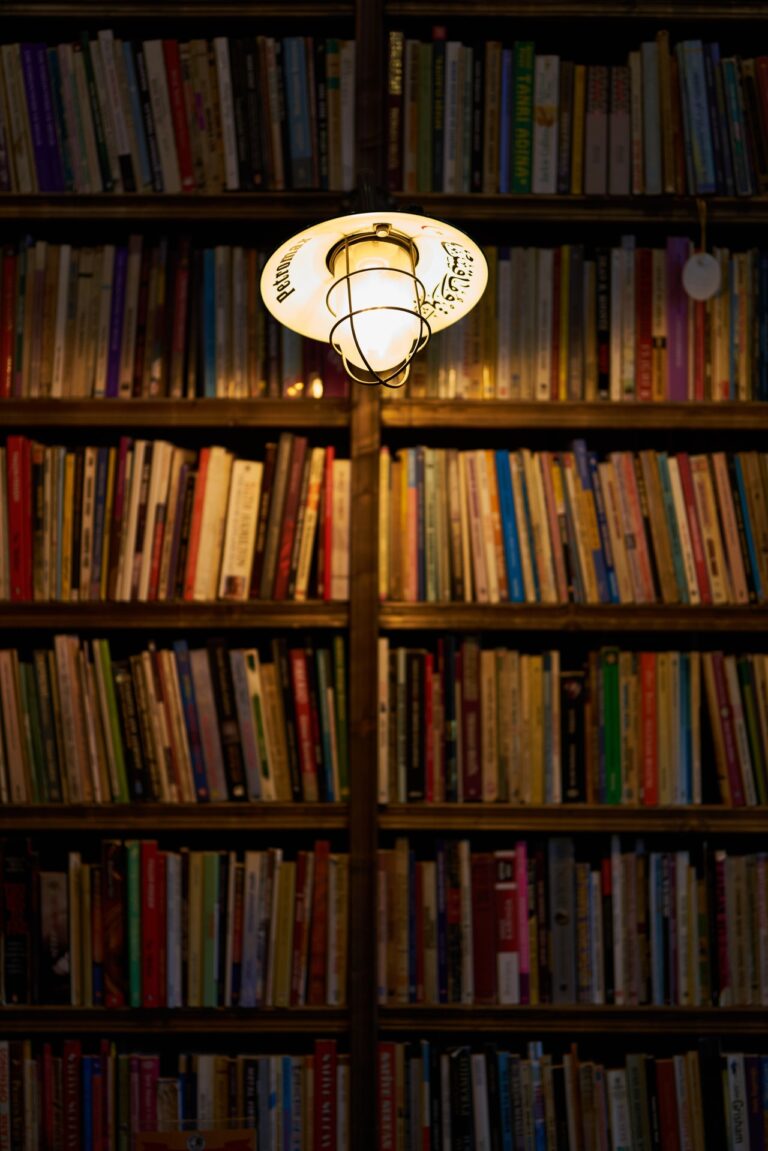

Images like these often come to me – uninvited, almost discovering themselves – while I wander in libraries. As a beginning researcher working on colonial-era English periodicals, my work demands a considerable amount of foraging for ‘material’ among shelves stacked with old, dusty volumes – often untouched in years, sometimes decades.

Often, after going through several such volumes, if I am lucky, I might find one essay that suits my topic – a joyous moment of discovery! It is easy to get bored and dejected when nothing shows up in volume after volume.

Yet, what sustains the will to keep searching is a sense of wonder, a belief in that quintessential nature of libraries and books to surprise – often at the unlikeliest of times and places, like when, at the IGML again, I stumbled upon an edition of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary published in 1773 – exactly two centuries before my university was established.

A belief in such surprises teaches some important life lessons in patience, perseverance, and humility. The ability of libraries to surprise unsettles the overconfidence that can sometimes develop when one works on a particular topic for a certain amount of time: a book, or an essay will invariably show up, that was always there, but had escaped notice. Thus, for a good library, one has never read enough!

A history of the borrower

A venerable professor of mine once reflected on the importance of serendipity to research – one often stumbles upon a research area quite by accident, after a chance encounter with a book or an author in a library. There are wonderful tales wandering all over libraries – in the books, on the tables, even on the walls.

Some years ago, a tattered old paperback lying abandoned on a table at the IGML caught my attention. That slim book was The Village in the Jungle (1913), the first novel written by Leonard Woolf, a British civil servant who served mainly in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), before becoming a writer, publisher, and politician in Britain, and the husband of the novelist Virginia Woolf. It was (and perhaps still is) an obscure book, rarely talked about, but one I read with fascination.

The innumerable kinds of stamps on books have their own tales to tell. Some of them tell us where the books came from, who gave them, in what form. For example, several books on America came to the IGML in the 1970s and 1980s as gifts of the American Studies Research Centre (now part of the Osmania University) and the United States Information Service at Madras and Bombay (now Chennai and Mumbai).

Being supported and funded by the US government, such ‘gifts’ could be understood as diplomatic measures to promote American soft power as part of their foreign policy (a ‘textual’ diplomacy of sorts).

Library books tell tales about people too – just glance at the borrower-slips in them to know who has borrowed them and when. Many of those who frequent libraries will admit having indulged in this practice of innocent voyeurism, which is in many ways like gossip – that other irresistible human urge.

Extended family members

Libraries remain wonderful for another essential feature common to all great tales – they create memories that readers carry with them and pass on to others in the tales that they tell. Amitav Ghosh fondly remembers his grandfather’s personal library in Calcutta, in his 1999 Pushcart Prize winning essay ‘The March of the Novel through History’. He writes: “The bookcases towered above us, looking down, eavesdropping on every conversation, keeping track of family gossip, glowering upon quarrelling children” (p. 287).

Ghosh’s description suggests that over time, the bookcases has grown into members of his family, silent witnesses to family drama, and “important props in the little plays that were enacted in their presence” (p. 288). The books, he suggests, conveyed prestige and social status, which often helped the family in such delicate matters as a “marital negotiation” (p. 288). He recounts his skirmishes with family members, who did not quite approve of his disturbing the library, which, for them, was only as valuable as the other pieces of furniture at their home.

Tapping the nostalgia

More recently, in early 2021, between two deadly waves of the coronavirus pandemic, the noted historian Ramachandra Guha delivered a lecture titled ‘A Lifetime of Foraging in Libraries and Archives’ at the Bangalore International Centre, where he spoke about the addictive nature of archival research.

The lecture was not so much about history and historical figures (Guha’s forte), nor was it a promotion of his latest book (often an occasion for many of his talks). It was Guha enthralling the audience with forty years of memories from libraries and archives – tales of librarians, books, cities, people, nature – all encountered (sometimes by chance) in connection with libraries, narrated with an unmistakable sense of childlike wonder.

In both Ghosh and Guha, libraries evoke nostalgia; collections of books transform into archives of memory. Today, as the pandemic seems to be easing (for the moment, at least), libraries have once again started welcoming visitors. They are slowly filling up with people looking for knowledge, for leisure, for stories. The books themselves never refused to meet anyone (despite the pandemic); they were always there; it was the virus that came in the way. The silent denizens of the library have always been welcoming, ready with new tales – worth wondering about, and wandering for.

Write to us at [email protected]