Dense in philosophy, the paintings of KT Mathai connect our life and lived times with death and timelessness.

Seance: A meeting at which people attempt to make contact with the dead, especially through the agency of a medium.

The dead surround the living. The living are the core of the dead. In this core are the dimensions of time and space. What surrounds the core is timelessness. – John Berger, On the Economy of the Dead

Maybe the world we live in now is better seen, felt and comprehended through death, or conversations with the dead. Relieved of the shackles of worldly rationality and bounds of social obligations, the dead are capable of offering the living reveries and re-visions, revelations and realisations.

They remind us of both the ephemeral and the eternal, the worldly and the other-worldly, inviting us into certain vital connections and conversations with the beyond; a beyond that is ever-present and ever-ready to open up to mediations and meditations. It is both a journey inwards into one’s self, and outwards in time and dreamwards in space.

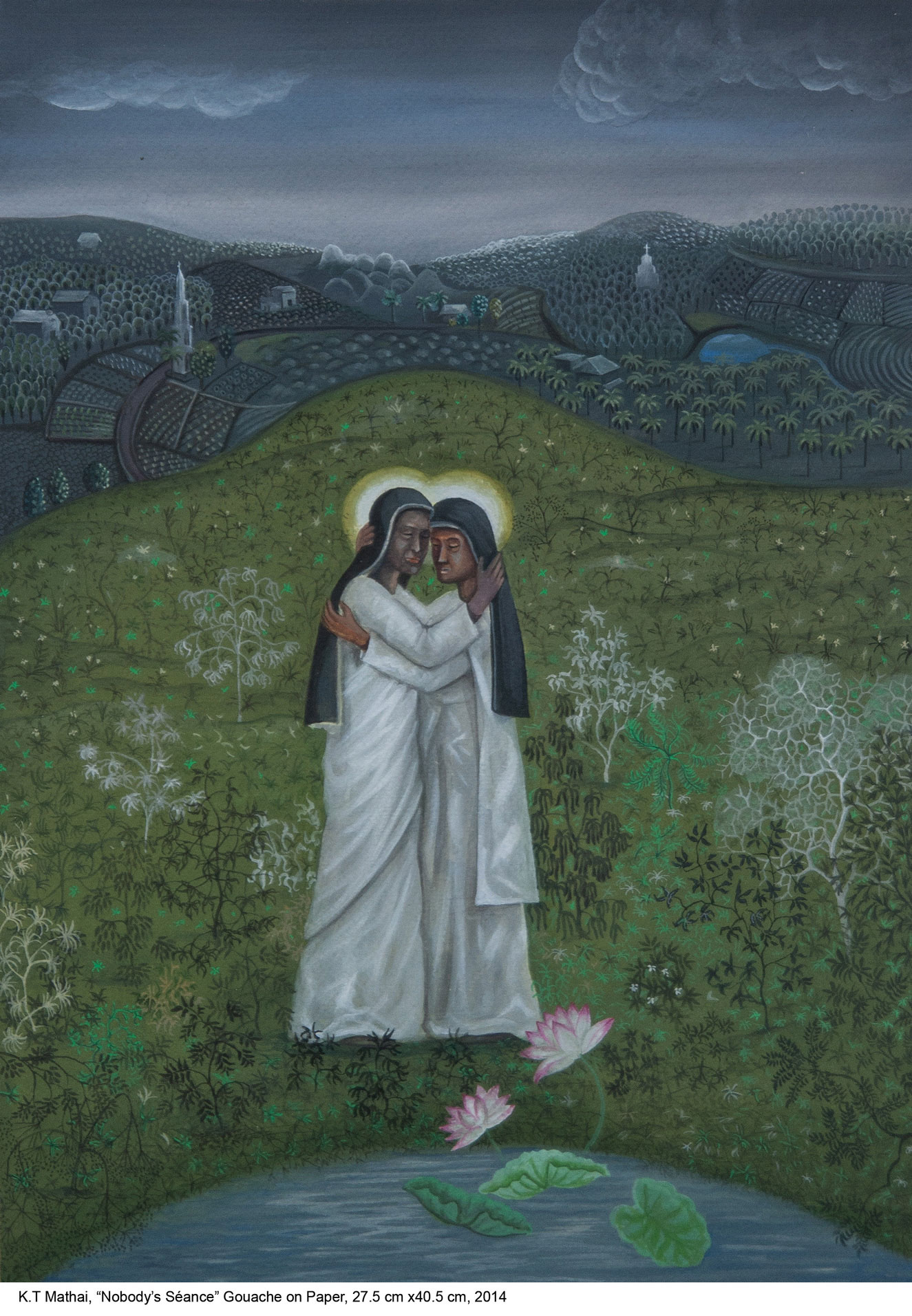

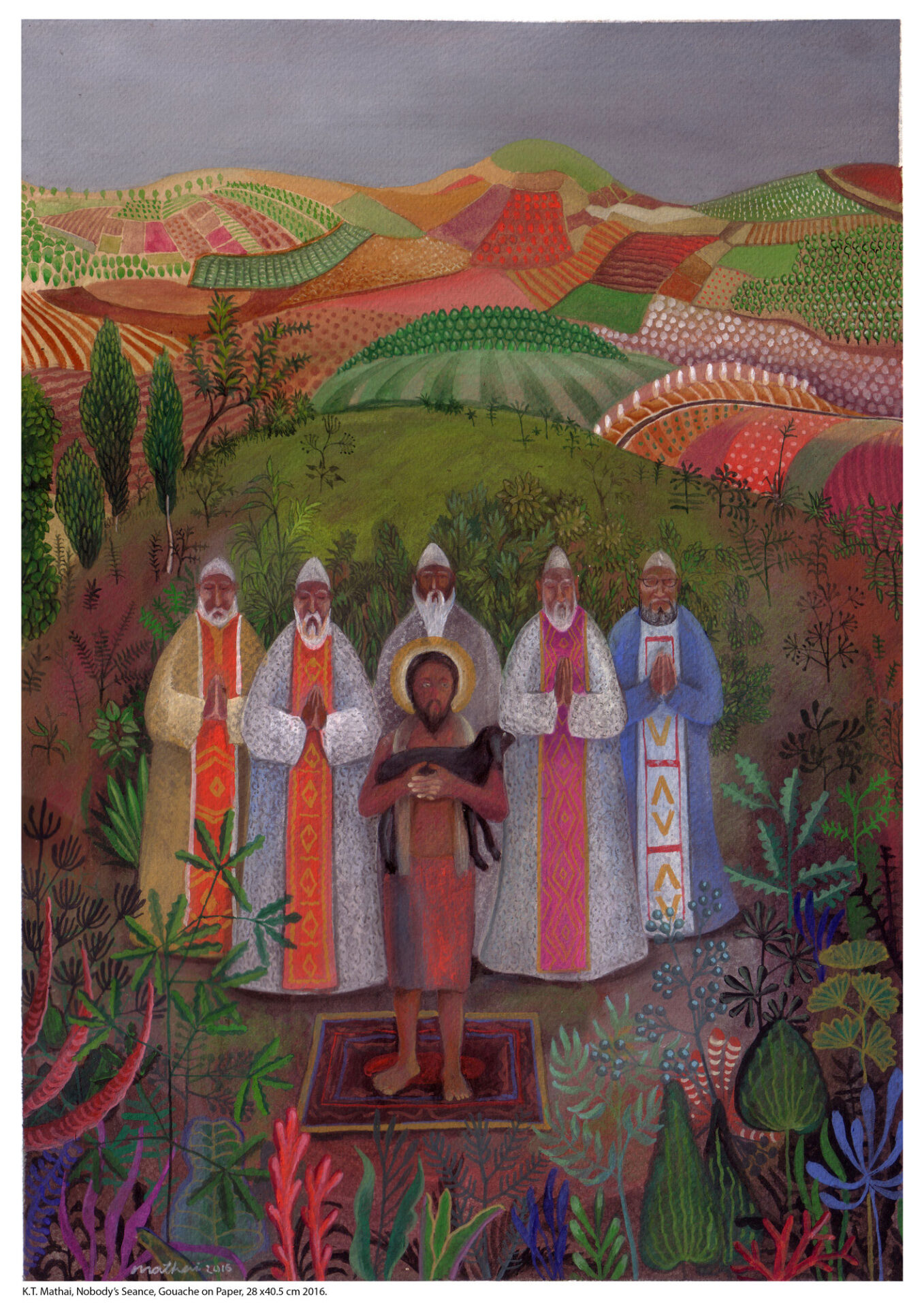

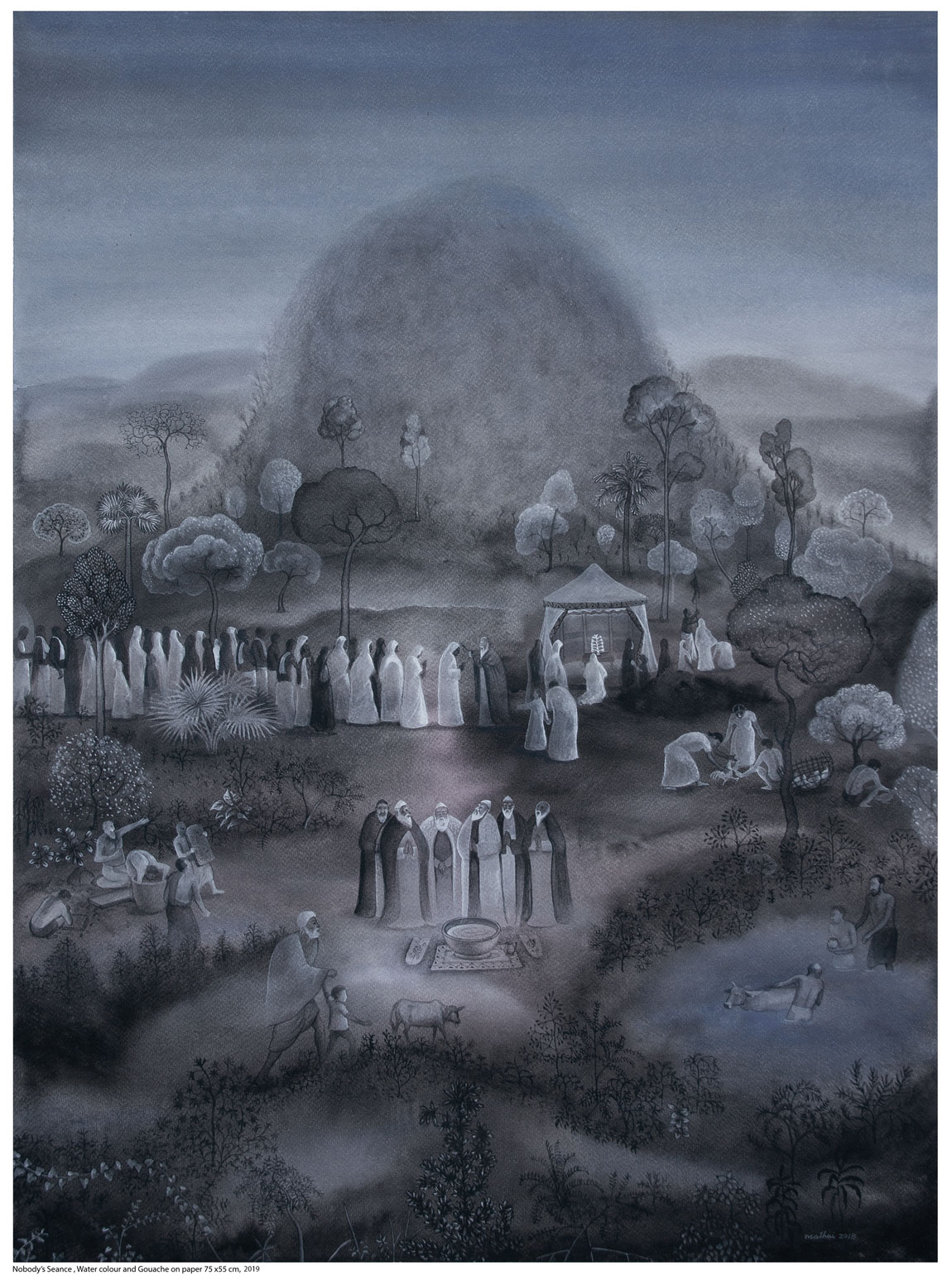

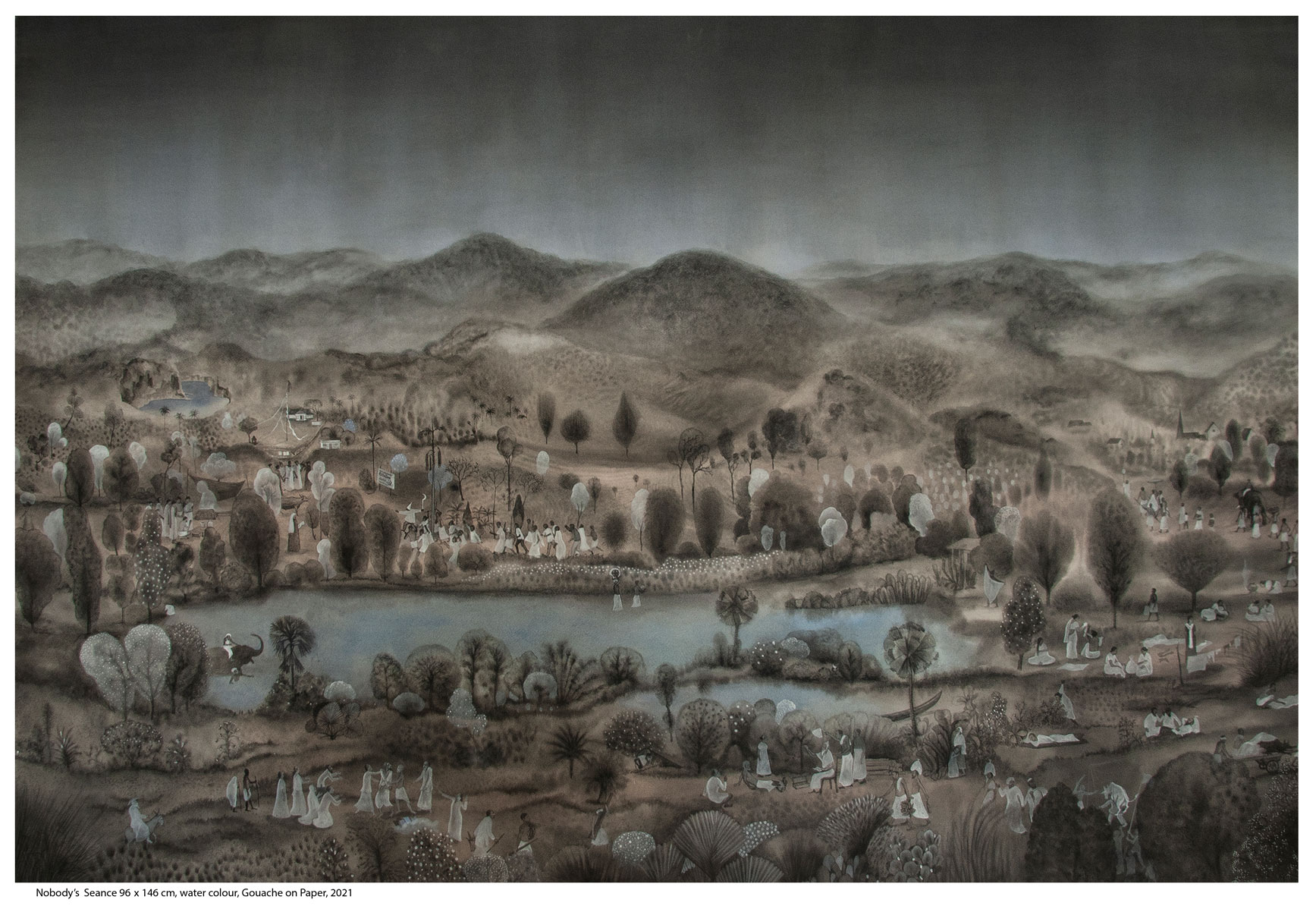

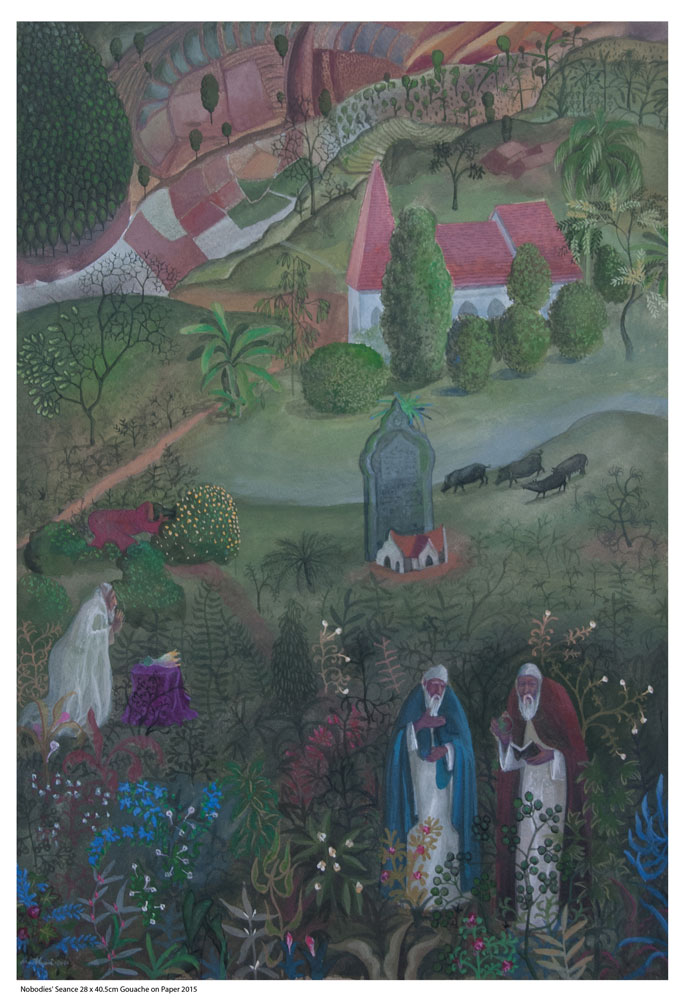

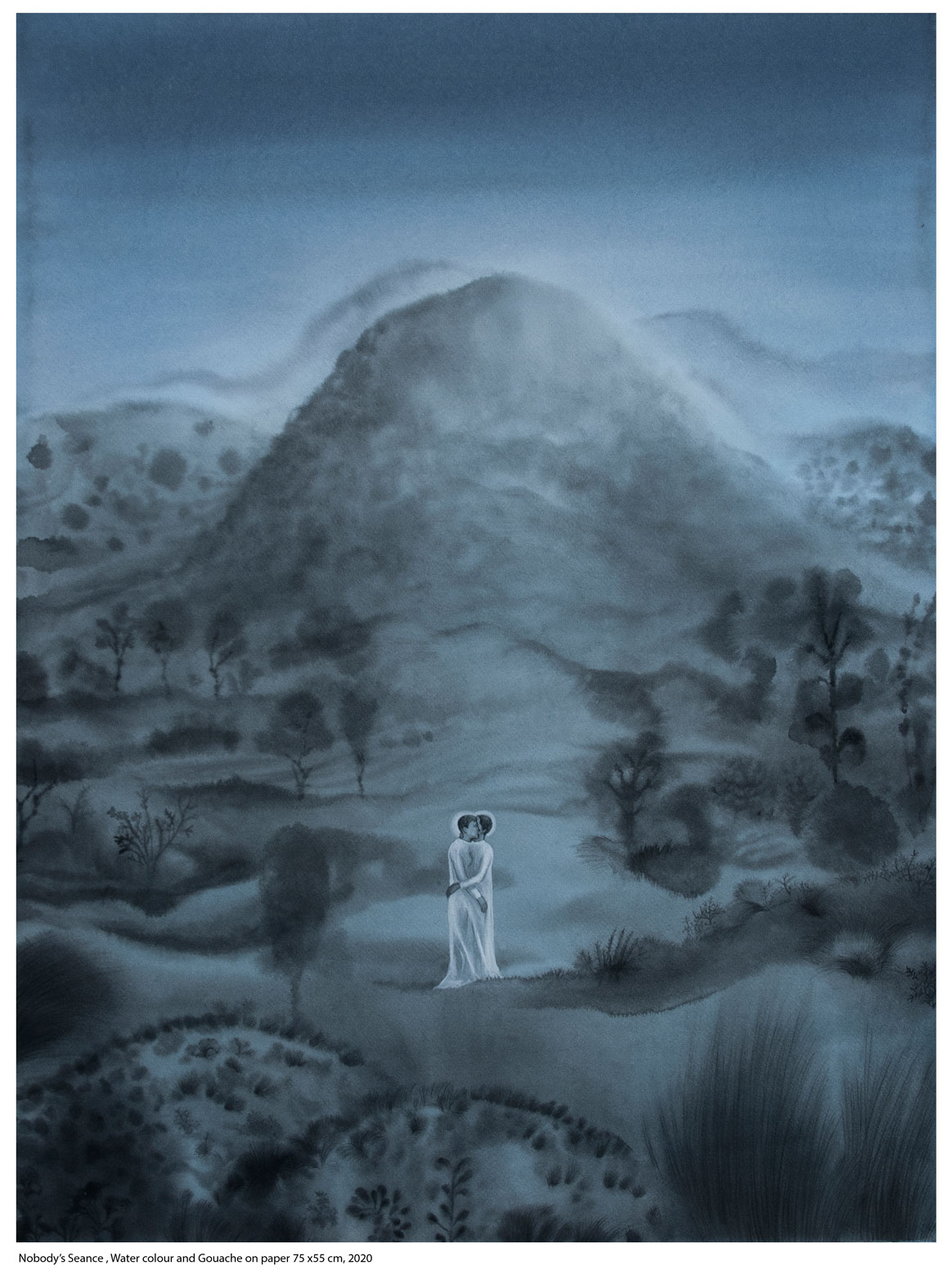

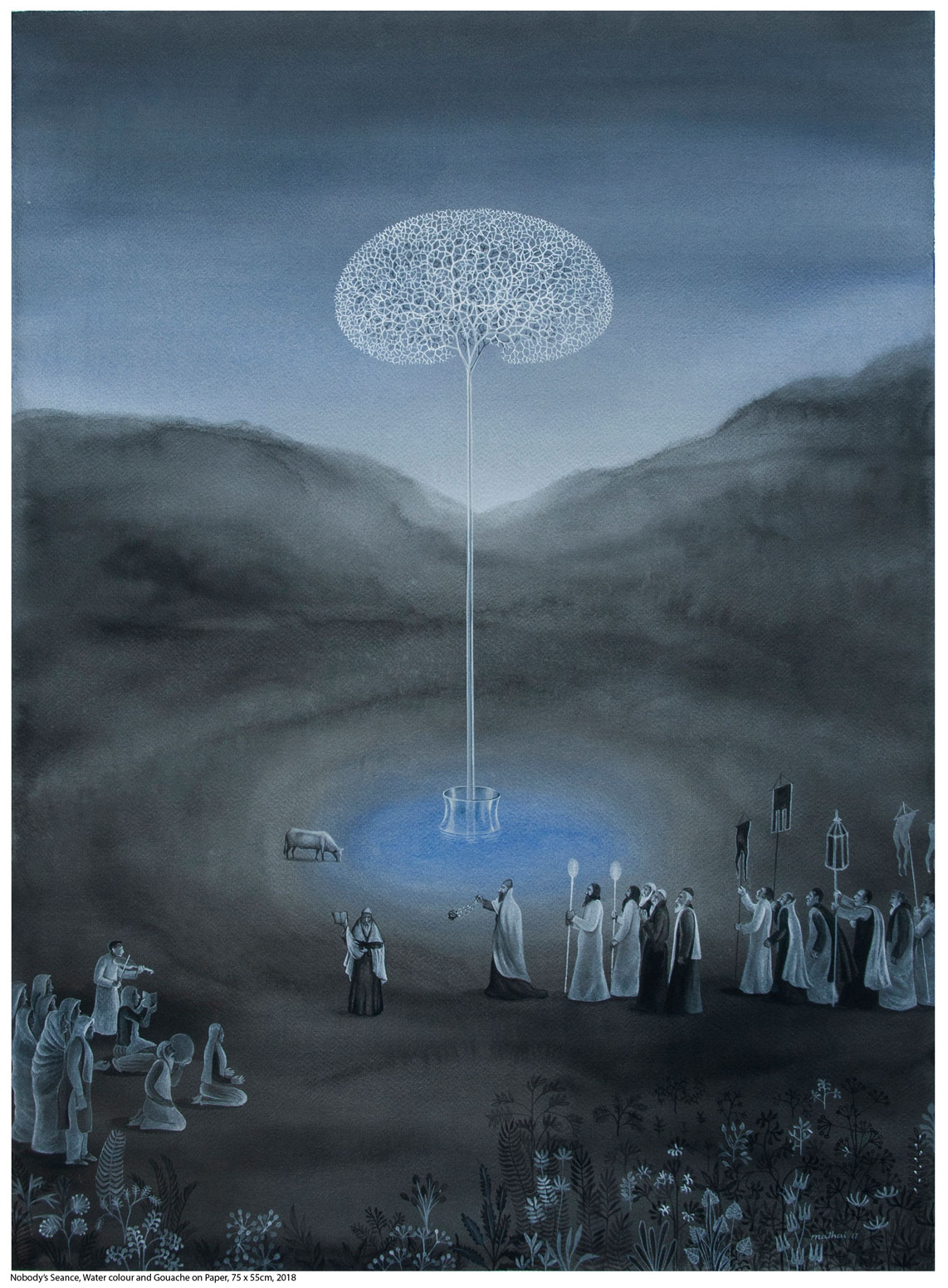

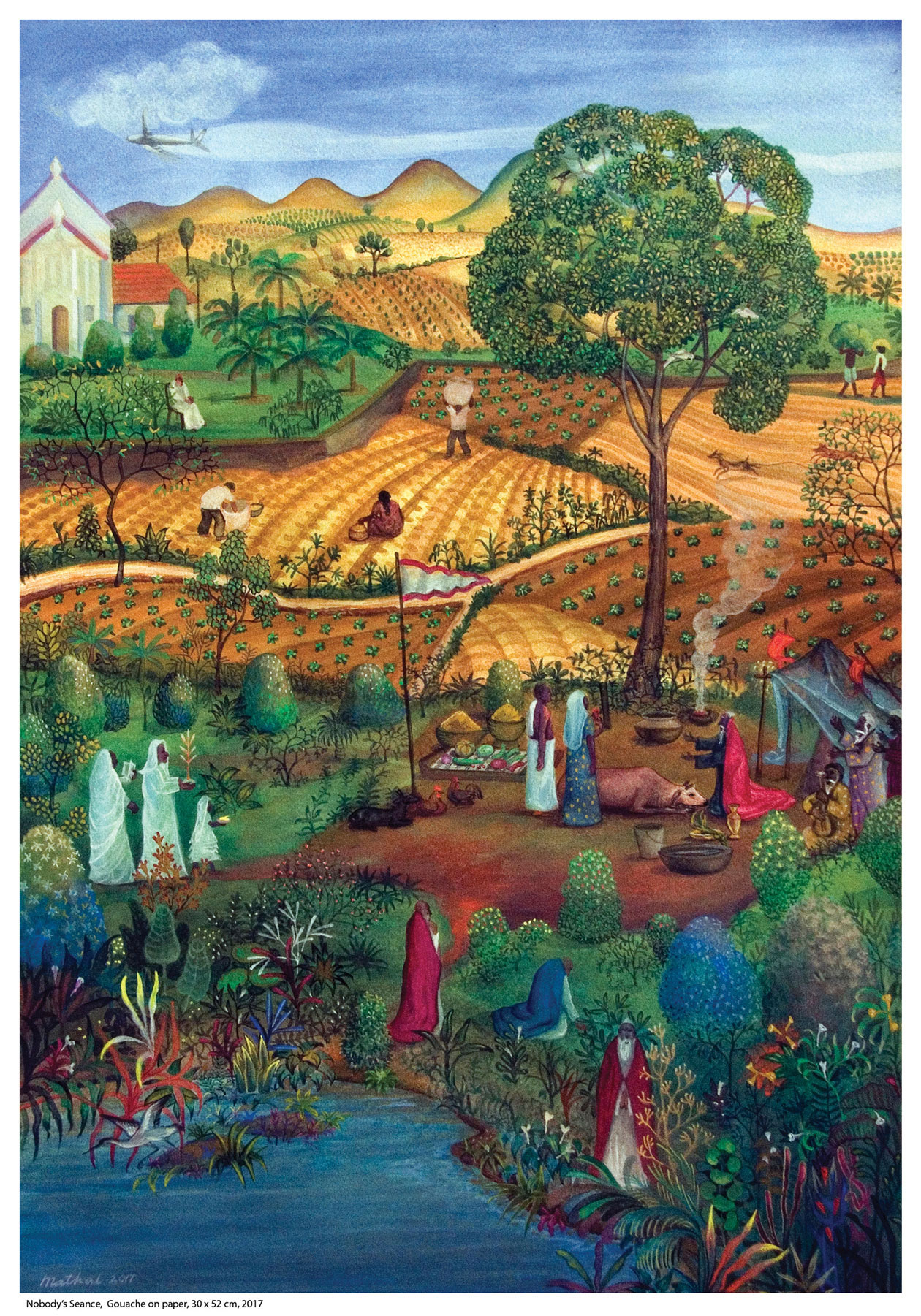

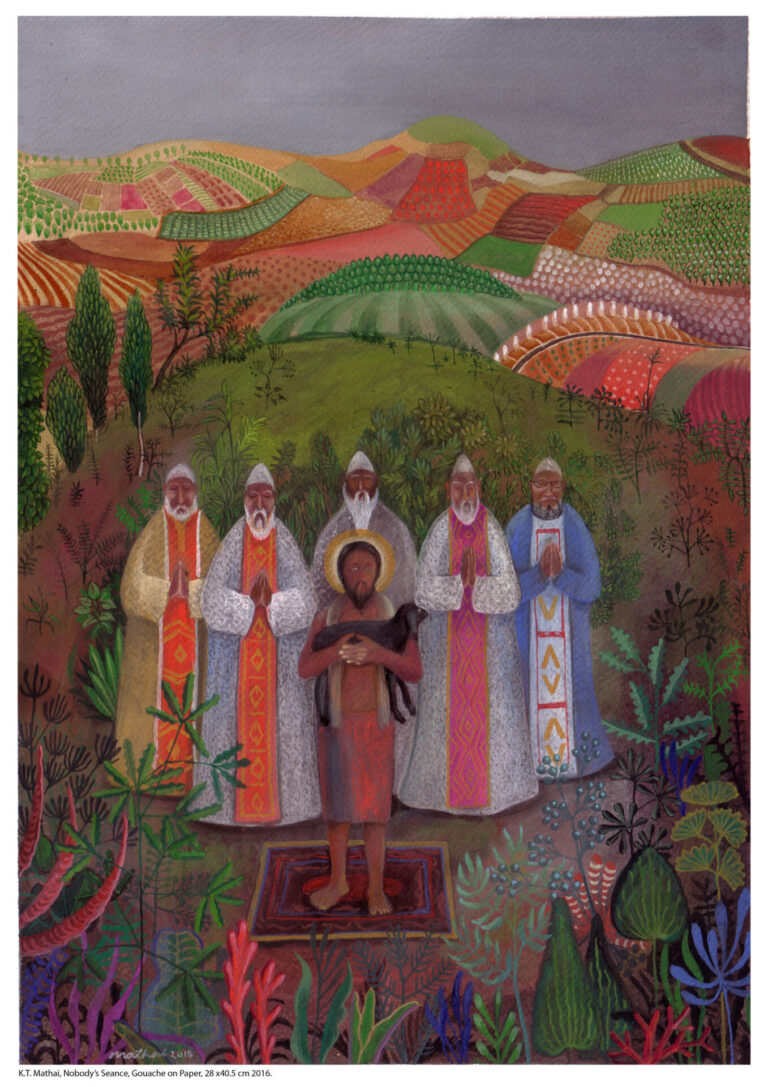

Mathai’s paintings titled ‘Nobody’s Seances’ exhibited at Lokame Tharavadu are epiphanic images that connect our life and lived times with death and timelessness. They are a series of oneiric visions: of spectral landscapes of different kinds, populated by human, animal and vegetal figures in different states of being, earthly and divine, visceral and ethereal.

The spaces are vast and magical, often with terraced landscapes extending to the horizon. In one set of images, the earth is green and laterite-red, deeply marked with the results of human labour in the form of ridges, various types of plantations, paddy fields, irrigated land etc. The other set of images is suffused with a certain dreamy luminosity, a twilight glow, invoking subliminal states of being between waking and sleep, dead and undead, dream and reality.

Mathai’s images

The terraced landscapes are layered vertically into the distance, and the space is filled sometimes with the stark light of high noon or inundated with a dreamy, hazy luminosity. In many paintings, a huge fountain of light shoots up from the ground and showers down from above. In some of the spectral dreamy-grey landscapes, a couple: they are nuns, priests, or Christ-like figures with aura above their heads, stand still oblivious of the worldly, yet deeply rooted in the world, in a deep sense of oneness and prayerful embrace.

In one of Mathai’s paintings where the earth-red and leaf-green dominate, the priests at pray are in ornamental vestments, with a christ-like figure standing at the centre, embracing a goat and intensely gazing at us.

In another painting, a large group of priests are gathered as if at a holy site; pilgrims are moving in procession to pray or receive blessings from the saintly figure; at the one side, a group of men and women are catching a fowl and on the other, a group of men are preparing tablet-like plaques; at another corner, an aged man is led by a child, and in a pond nearby, a man is washing a cow while two other men — one holding a sacrificial pot in his hands — are descending into the waters. In the background, a hill dominates the scene, surrounded by trees and covered in a bluish grey haze.

The composition of the image with the spiritual activities figured across with the prayerful actions at the centre all create an upward soaring of our gaze akin to a prayer.

In another deeply tranquil image by Mathai, we see a lean tree rising from the centre; a bluish pond — like a pool of light — is seen in the foreground while the rising hills loom in the background; a priestly figure is caressing the leaves as a spotted deer watches the scene in rapt attention.

Memory of the dead

The vertical and horizontal forces are pronounced in Mathai’s images. While the vertical force is divine and otherworldly, soaring up from the waters or the soil to the open skies and horizons, the horizontal structure composes this-worldly spaces, lands, formations, fields, flora and fauna.

For instance, the divine fountain of light, or the tree of life rises vertically, the earth ploughed, terraced and cultivated by human labour stretches out horizontally. These seemingly contradictory pulls also belong to the register of the human and the divine, the dead and the undead.

In most of the paintings of Mathai, like in murals or miniatures, there are multiple planes — skies, waters, earth, vegetation and built structures — and different moments of action scattered across the canvas, of various actions and gestures of people praying, preparations for rituals or sacrifices, making offerings etc.

As our eyes roam over or circumambulate the image, we are transported into the mood and occasion of a seance, where we begin to converse with the dead. These sublime congregations and our conversations with them are not visitations into the beyond, but rites of passage that sublimate and renew us.

They bring us back to our world and life, heightening our feelings for and awareness of the festive, solemn, or penitential nature of our experiences and actions. As the guidelines for preparing the liturgical environment insist on decorations, these images too draw us “to the true nature of the mystery being celebrated rather than being ends in themselves.”

To return to John Berger, “The memory of the dead existing in timelessness may be thought of as a form of imagination concerning the possible. This imagination is close to (resides in) God, but I do not know how.”

1 Comment

Good wrk in meat event v