From Lanka to Rajasthan to Persia to Norway, the ravanahatha’s journey over eons has been astonishing, even intriguing

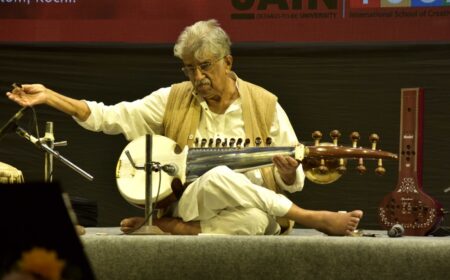

For what may appear to the average westerner as an Indian version of the violin, the ravanahatha has its timbre loser to the sarangi’s in Hindustani classical. The folksy string instrument with a bow belongs to a region which is part of Rajasthan and Gujarat. Effectively, the ravanahatha resonates with the ethos of the barren or semiarid expanses of the two states.

Now, arguably a more interesting aspect of the story. If the first part of the name of the instrument reminds you of the antihero in the Ramayana, it’s still a mystery how the mythological Lankan emperor found a place on the cultural map of India’s northwest.

Lankans largely differ. The Sinhalese as well as the immigrant Tamils. Going by historical sources with Hela, the Indo-Aryan ethnic group in Ceylon, the island-nation is the native place of Ravana. The public largely see Ravana as a Dravidian asura, who was an unflinching devotee of Lord Shiva.

Purana tale

Such was Ravana’s bhakti that he regularly sang prayers invoking the God of Destruction. With a stentorian voice, he would play a string instrument while worshipping his lord. Once he had to pull out a vein from one of his 20 hands to strum it and produce music. That was when the king had his palms crushed under the Kailash he tried to lift, but failed when Shiva who lords over the mountain pressed his thumb toe in retaliation.

Hath in Hindustani language is a derivation of the Sanskrit hasta, meaning hand. Ravanahatha, in short, was the Lankan king’s musical instrument.

So, how did the supposedly Lankan instrument emerge as a major presence in northwest India? Again, legend has it that monkey-god Hanuman as a devotee of Rama who killed Ravana took the instrument far up the island. In present days, ravanahatha is central to the nomadic culture of Rajasthan. Its street musicians play the instrument in solo as well as groups or as backdrop to traditional puppetry. Manganiyars are a tribal community who have mastered the ravanahatha.

The perceived transportation of the ravanahatha from Lanka has a post-script. According to certain scholars, the instrument worked as the prototype for the Arabianrebab, courtesy traders from West Asia during the 8th and 9th centuries AD.

The make

In its new-age version, the ravanahatha has a bowl-shaped resonator and a longish bamboo stem besides its strings and, of course, the bow. While a cut coconut shell functions as the resonator that is covered with goat hide, the 80-cm body is punctuated with knobs at regular intervals. Plus, there is the banjara, smoothened hair from horsetail, which gives the ravanahatha its individualistic sound. The bow often features bells for the performer to keep the rhythm.

Middle-aged Bishna Ram is one ravanahatha artist, whose Bhopa Bhil tribe family has been into making the instrument for generations. Besides the traditional ditties, he plays contemporary numbers. Often they sound melancholic. “We aren’t sure how long our art will survive,” he sighs. “There must be a new system of patronage in

modern society.”

New-age Innovators

If Bishna Ram sounds despondent, not so does Dinesh Subasinghe. The 41-year-old is a Sri Lankan composer-violinist. Using the ancient instrument, his albums are earning international fame over the past two decades. Especially remarkable are Subasinghe’s Rawan Nada and the Buddhist oratorio Karuna Nadee.

To the Colombo-based artiste, there is a reason if the ravanahatha sounds blue. “I’d say it echoes Ravana’s mind, being portrayed a ruthless villain when he was a scholar with artistic capabilities. A tragic hero,” he says.

Young Chennaiite composer Leon James, too, is excited about his repertoire featuring the ravanahatha. The 28-year-old, whose father was manager of world-renowned music producer AR Rahman, says the internet enabled him to stumble upon the ravanahatha. “I bought it from an artiste in Jaisalmer,” he reveals, referring to the gold-hued Rajasthani fort of the 12th century.

Leon arrived in the industry with a Tamil movie released in 2015, when far away, in the Netherlands, author Patrick Jered released a book based on the ravanahatha. Titled Finding the Demon’s Fiddle, the researcher refers the instrument to an early precursor to the violin, thus agreeing with septuagenarian musicologist Joep Bor, who is a sarangi exponent as well.

Scandinavian band Heilung, whose members are into experimental folk music, too employs the ravanahatha.

Write to us at [email protected]