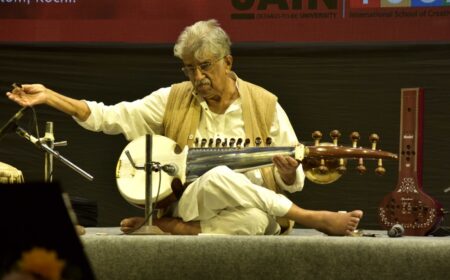

On carnatic musician N P Ramaswamy’s first death anniversary, a take on his art vis-à-vis the heritage of his West Kochi.

N P Ramaswamy was born in the year that gave British-ruled India its last “proper” census. The 1931 headcount, which particularly scanned the country’s multiple castes and ethnic groups, holds no direct relation with the Carnatic musician, but for the place, he happened to grow up.

Kerala’s Mattancherry, along with adjacent Fort Kochi, has no less than 30 communities living harmoniously for seven centuries. The twin towns’ history of immigrations shows in the 16-odd languages spoken by its residents in a radius of just 4.5 square kilometres.

So, in the first quarter of the 20th century, when a Brahmin family of Tamil ancestry joined the melting pot, syncretic Mattancherry imbibed a new Carnatic tradition. A job in a chemical products company led Ramaswamy’s father to move into the place, now in Ernakulam district.

The man, NPR Iyer, was an officer with Pierce Leslie India. Iyer sang but wasn’t a professional vocalist. His father, however, was a musician of high reputation. Palakkad Parameswara Bhagavathar (1815-92) had gone on to become the chief palace musician of Travancore kingdom at a young age. That was towards the last years of the art-patronising Maharaja Swathi Thirunal’s reign in the first half of that century.

Ramaswamy’s lineage boasts of not just an inheritance of music. The family’s recent past is defined by frequent resettling: from Tamil Nadu to Nurani to Padmanabhapuram (royal abode near Kanyakumari) to Kochi.

Iyer’s busy working schedule didn’t mute his interest in music, but he thought he was a bit aged to learn Carnatic formally. Yet, the house resounded with south Indian classical owing to the next generation, Ramaswamy used to recall.

Today (November 5) is the artiste’s first death anniversary.

Self-groomed skillsets

The stature Ramaswamy (1931-2019) gained as a vocalist and lyricist-composer bears a surprise: he had no teacher after the prelims. “My father was my only guru, strictly speaking. He used to say I sang well as a four-year-old, and would even name the notes,” Ramaswamy recalls in a 2014 interview. “That was on hearing my father teaching my elder sister.”

Into his youthful days, besides through the radio, Ramaswamy got exposed to Carnatic concerts around Kochi. He and fellow buffs founded a music forum called Gosri Gana Sabha in Mattancherry in 1967, which had a precursor: Cochin Fine Art Society. The guest performers stayed at Ramaswamy’s house.

Alongside the records of those kucheris, Ramaswamy began learning kritis by their notations. Masters to effectively become his gurus included Alathur Brothers, G N Balasubramaniam, M L Vasanthakumari, D K Jayaraman, S Kalyanaraman, M Balamuralikrishna, R K Srikantan, Nedunuri Krishnamurthy…. “My manasaguru, though, was K V Narayanaswamy. I liked him the most,” according to Ramaswamy, who has sung three times at the prestigious Navaratri Mandapam concert series by the Padmanabha Swamy temple in Thiruvananthapuram.

An MSc in applied chemistry, the musician worked with a pharma firm in Kochi. He retired in 1991. As a septuagenarian, he unexpectedly lost his wife Prema Ramaswamy. The gloom eventually forced him to find refuge in a new creative engagement: penning books on Carnatic. Ramaswamy came out with five printed works: Techniques of Manodharma and Swaras Made Easy, Swara Sancharas of Popular Janyaragas and Meaning of Dikshitar’s Navagraha Navavarana Kritis being the first.

Next, Ramaswamy compiled his own compositions: 20 varnams, 30 viruthams and a few thillanas. His fag-end engagement was with setting jantavarisais (basic traditional scalar twin-note exercises) for janyaragas (melody-types derived from parent scales). His felicity with Sanskrit compositions gave him the name ‘Kerala Dikshitar’. Dwijati Tripura was a tala invented by Ramaswamy, who won Kerala government’s Sangeetha Nataka Akademi award.

Mattancherry heritage

Ramaswamy had a singing repertoire of 1,500 compositions. He performed even towards the evening of his life but wasn’t pleased with a “commercial culture that set” into Carnatic. He taught pupils individually. “In groups, you can’t correct them,” used to be his refrain.

Historians point out the unique mix of cultures in West Kochi. They note it is the world’s only place to be ruled by the Portuguese, Dutch and the English (in succession). A 1343 flood led to Kochi’s evolution as a natural port. As commerce grew, Mattancherry and Fort Kochi became settlements for generations together from various parts of the subcontinent and the world.

The trend keeps earning the coastal pocket many layers of culture. Ramaswamy’s contribution to it isn’t small.