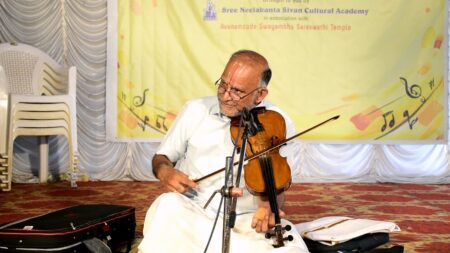

Mridangam Maestro Parassala Ravi is known for blending tradition with innovation in his playing style. At the age of 80, his authoritative voice in the art of mridangam resonates with both strict discipline and deep camaraderie with his students. With decades of teaching experience at prominent music colleges like Tripunithura RLV Music College, Palakkad Chembai Memorial Music College, and Thiruvananthapuram Swathi Thirunal Music Academy, Ravi has mentored countless students across Kerala. “I am a strict teacher in class, but also a friend to my students. I encourage them to ask questions, even if it’s on the street. This openness is essential in learning any art form, as it was in my own journey,” says Ravi.

How did your journey with mridangam begin?

My mother, Gomathiyamma, was a music teacher, and my father played the nagaswaram. We lived in Kuzhithara in Kanyakumari, then part of Travancore. My father hailed from Parassala, and my mother from Padmanabhapuram. I studied in Kuzhithara School until the 5th standard, where my mother taught, and then continued in Parassala. Music was in our family—my maternal grandfather was a nattuvanar at Padmanabhapuram Palace, and I learned the basics of rhythm from him. Observing him, I understood the differences in playing for Bharatanatyam and Carnatic vocal performances.

In high school, I had a friend who played the ghatam. We used to sit at opposite ends of the bench and tap out rhythms on the desk, imitating each other. That’s how it all started for me. Later, a mridangam master named Kaliyappan Annavi came to our village from Tamil Nadu. I expressed my desire to learn the mridangam to my father, and he arranged for me to start lessons. I had a mridangam but no cover for it, so I carried it on my head and walked a kilometre to class. Unfortunately, after two years, my master couldn’t continue teaching due to ill health, so I began learning from another master who also played Thavil.

I failed my 10th standard, and my father was furious. I wanted to leave home, so I told my mother I wanted to study at the Swathi Thirunal Music Academy in Trivandrum. My maternal uncle, who was a neighbour of Mavelikkara Velukutty Sir, took me to meet him. Velukutty Sir asked me to play, and I performed a chollu in three speeds. Although the admission was closed for that year, Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, who was the principal, made an exception for me. That’s how I got enrolled in the Ganabhushanam course.

Later, I received a scholarship from the Devaswom Board and used it to buy a mridangam. I started taking on students to earn money and accompanied Velukutty Sir for various programmes. By the time I completed my course, I had already started performing at small events.

You also played the ghatam and kanjira. How did that come about?

When I was in my second year, my guru took me to a concert where the ghatam artist didn’t show up. My guru asked me to fill in, and I agreed even though I had never played the ghatam before. I played it as I would a mridangam, and it turned out well. After that, I played the ghatam in several concerts.

Once, I was asked to play the kanjira instead of the ghatam. The kanjira is different from the mridangam and ghatam, as it is played with a single hand. I struggled during the taniavarthanam and was disappointed. The next day, I bought a kanjira and started learning it. Over time, I played kanjira with many renowned mridangists but eventually focused on the mridangam.

Is the gurukulam method or university learning better for mridangam?

The gurukulam method is best for learning traditional art forms like mridangam. It doesn’t necessarily mean living at the guru’s house and doing chores but involves closely following the guru. Learning in a gurukulam isn’t bound by classroom hours. It’s about absorbing the guru’s teachings, observing their playing style in concerts, and learning in the spaces between formal lessons. My time with Velukutty Nair was like that—learning on the way to concerts, clearing doubts during bus rides.

I follow the same method with my students. This approach is more serious and often leads students to pursue mridangam professionally. The university system confines learning to the classroom, which limits the depth of understanding, and fewer students continue with the art form long-term.

What defines the Parassala Ravi Baani?

When someone, driven by the energy of their learning, shapes their own path, a unique style is born. In my books, Mridanga Bodhini, Mridangatinte Thani Aavarthanam, and Mridanga Padanam, I’ve documented the rhythmic insights I’ve gained through years of experience. I’ve developed and organised methods for effortlessly creating moras and korvais. By experimenting with these techniques, one can explore the vast possibilities of mridangam and showcase its diversity.

When I teach, I emphasise the importance of preserving creativity. If a student simply copies what I teach, that’s not what I want. They need to create, innovate, and develop their own style. All my students are capable of this. A more aesthetic playing style will endure.

Even students learning from the same teacher will have different styles. Tradition is the foundation, but on top of it, there should be innovation—that’s the true talent of the player. As a guru, I guide my students on what is right and wrong without changing the style. I show them the path and the possibilities. People often recognise the performances of my students as embodying the ‘Parassala Ravi Baani.’ This is how a baani (style) emerges.

What do you think about the innovations in Carnatic concerts?

Thaniavarthanam has a specific structure, and korvais should be played in their place. But when playing for songs, it’s about the player’s manodharma. Mridangists should have a strong knowledge of music. Some musicians sing at a very fast tempo, and the mridangist must match that energy. The old style of singing is fading, and with it, the style of mridangam playing is also evolving.

Now, concerts seem to give more importance to accompanying artists, sometimes even overshadowing the vocalist. What’s your view on this trend?

In a vocal concert, the vocalist should always be the focus. Accompanying artists should support the main artist without overshadowing them.

You’ve accompanied many artists. Who have you enjoyed playing for the most?

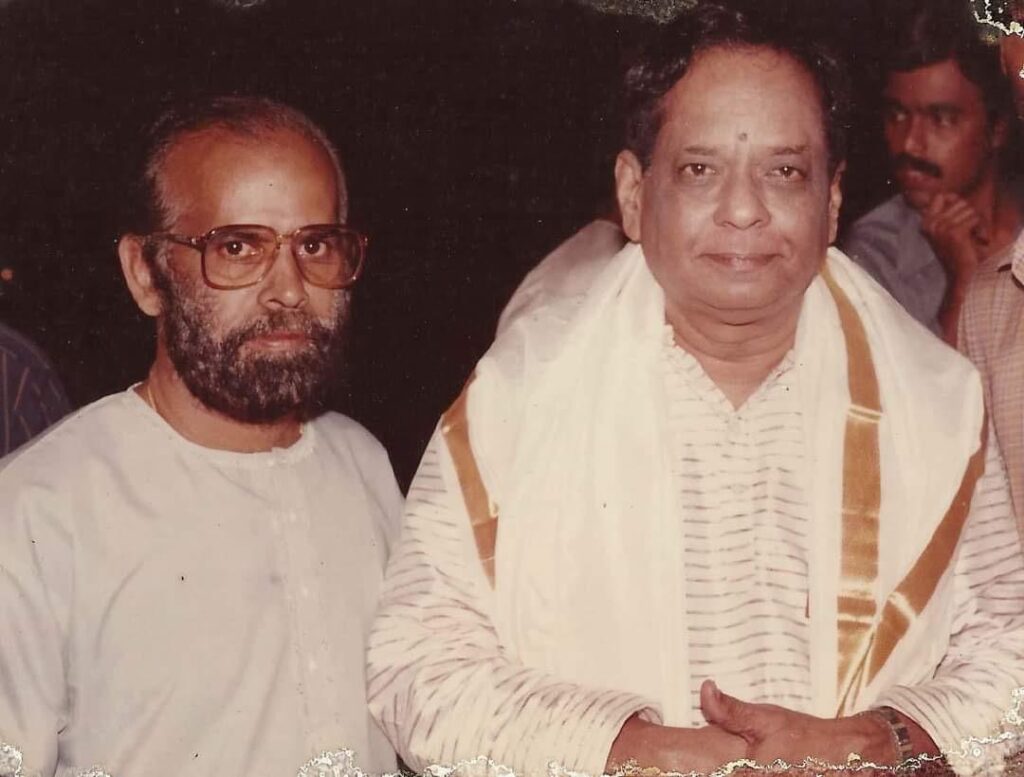

I’ve played for most of the senior artists and many from the past generation—Semmangudi, T. N. Seshagopalan, R. K. Srikantan, Chembai, and so on. Chembai was a versatile singer who never missed a chance to crack a joke. Semmangudi’s music could move listeners to tears. No one could sing kalapramanam like M. D. Ramanathan, and M. S. Subbulakshmi’s music is a pleasure to the ears. Each artist has their unique qualities.

You received two major honours this year. Sangeetha Kala Acharaya from the Madras Music Academy and Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Academi Fellowship. How do you feel about them?

Recognition brings happiness, but it doesn’t change who I am. I’m the same person I was last year. Awards don’t change a person; they just acknowledge their work.