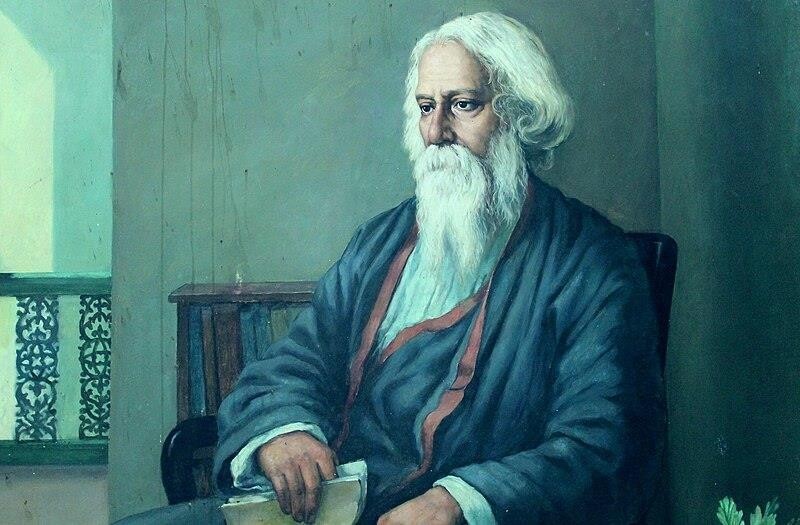

The enchanting cross-cultural dance form of India’s first Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, Rabindra-nritya, has crossed boundaries and delighted audiences worldwide.

In the realm of artistic legacies, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) stands not only as India’s first Nobel laureate celebrated for his literary and artistic brilliance but also as a trailblazer of a mesmerizing dance form known as ‘Rabindra-nritya.’ As part of his multifaceted contributions, Tagore composed four dance-dramas – Chitrangada (1936), Chandalika (1938), Shyama (1939), and Shrabangatha – where captivating stories unfurled through the enchanting language of dance and song. This distinctive dance form, a creation by Tagore himself, defies easy classification, blending classical roots with a contemporary essence. With its graceful and fluid movements, Rabindra-nritya weaves a tapestry of emotions that irresistibly captivates the eye while the soul is serenaded by melodious poetry.

The costumes used in this dance form are adaptable and can be changed according to the character or song being portrayed. The musical support comes from Rabindra sangeet/nritya-natak, compositions by Tagore. While Rabindra-nritya was initially limited to the four dance-dramas, it has now expanded to include many other songs composed by Tagore. These dances are not only performed at Santiniketan, where Tagore established his school, but are also featured in films, cultural programs in Bengal, Tripura, Bangladesh, and even in other countries. Enthusiasts of this dance form also showcase their talents through videos based on Rabindra sangeet on platforms like YouTube. Moreover, Durga pujo celebrations in some states include Rabindra-nritya performances in their cultural programs, delighting audiences both in India and abroad.

Evolution of Rabindra-nritya

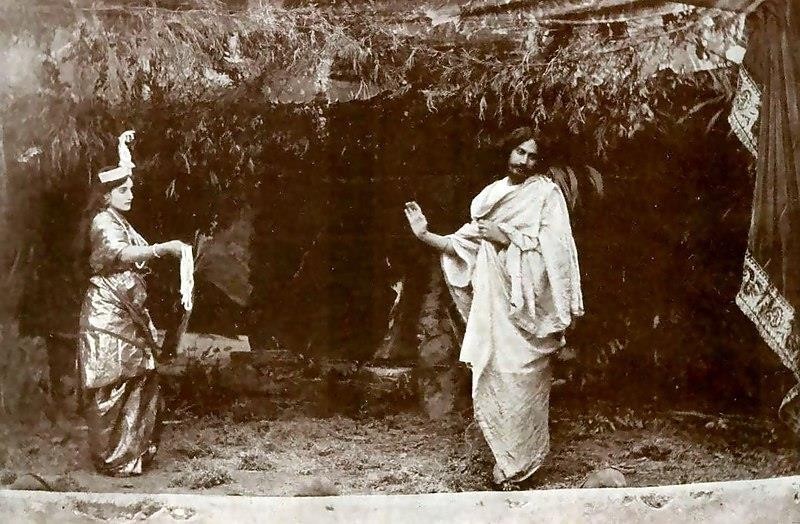

In a study by Utpal Banerjee in 2007 on Rabindra-nritya, Santidev Ghosh, who spent three decades in Santiniketan, chronicled dance-related events in Tagore’s life. In his teenage years, Tagore had visited England, where he was exposed to Western dance. Inspired by figures like Spenser and Weinet, he wrote dramas in 1881. In 1901, he established Santiniketan, where he encouraged his pupils to dance. With the founding of Visva Bharati in 1925, dance teachers were engaged to instruct the students. Tagore himself appeared on stage in his dramas and musicals. He composed numerous dramas such as Natir Puja (later adapted into a film), Tasher Desh, and Shapmochan, which were mainly depicted through dance. In his senior years, he focused on composing pure dance-dramas like Chitrangada, Shyama, and Chandalika.

Tagore’s exploration of different cultures significantly influenced his dance form. He gathered knowledge from various places, including Manipur, Cochin, Malabar, Java, Bali, Thailand, China, Burma, and Sri Lanka. His dance initiatives showcased Bengal’s folk-dance idiom. However, Tagore faced criticism for featuring feminine talent on the public stage, although he supported gender equality and challenged untouchability through his dance idiom. While Tagore did not leave specific choreographic leads, Valmiki Banerjee reconstructed the vocabulary and set the sequences according to Tagore’s vision.

Tagore’s dance form embraced cross-cultural elements, and his exposure to Western dance during his stay in England had a significant impact on his style, especially in understanding ‘staccato’ through Herbert Spenser’s work. He also drew inspiration from Richard Wagner’s introduction of text-based songs in opera, evident in his traditional opera Mayar Khela, where the songs could be sung independently. Western music was also incorporated into his works, such as Raja and Achalayatan in 1911. Tagore’s dances celebrated the cycle of seasons, bringing joyousness to the stage during the ‘festivals of seasons’ held in Santiniketan in 1919, which later became part of the study curriculum.

Dance-dramas and their themes

In Chitrangada, Rabindranath Tagore embellishes the character of Chitrangada from the Mahabharata, portraying the different emotions of a woman who, as the princess of Manipur, marries the Pandava prince Arjuna during his exile. The dance-drama effectively conveys this story through dance and song alone, making it one of Tagore’s most popular dance-dramas. Chandalika, another well-received dance-drama, is based on a Buddhist legend about Ananda, one of Buddha’s disciples, and his encounter with Chandalika, a girl from a lower caste who offers him water to drink. The story has social implications for both characters.

The girl is grateful for the monk’s acceptance of water from a low-caste girl and uses magic to make him attracted to her. However, when the monk visits her home, he feels ashamed and seeks Lord Buddha’s protection to break the spell, thus escaping the intended fate. Shyama depicts the story of a court dancer who falls in love with a foreign merchant named Bajrasen, and she faces various challenges in her quest to win his love. These dance-dramas are unique as they rely solely on dance and song to convey their narratives, with no spoken words. Experts classify these works as pure dance-dramas in Tagore’s repertoire.

A cross-cultural endeavour

Rabindranath Tagore’s return from Java in late 1927 marked a transformation in his dance initiatives. The simplistic Varsha Mangal (Ode to the rains) and earlier celebrations evolved into Rituranga (Splendour of the seasons) with Javanese nuances. The incorporation of different styles resulted in a medley, including Gamakas and Khol rhythms for group dances, along with elements of Kathakali and Baul. Notably, Pratima Devi, Tagore’s daughter-in-law, traveled to the UK to study European modern dance under Kurt Joss, a student of Rudolf von Laban, and introduced cooperative choreography to blend various dance idioms. Srimati Thakur, associated with Santiniketan’s seasonal celebrations between 1920-27, trained in European modern dance during her visit to Germany.

Additionally, Elizabeth Sass Brunner, a Hungarian resident, performed Rabindra-nritya to the song “Ami chini go chini tomare…I know you, I know you, o foreign lass…”. Tagore’s magnum opus song and dance-dramas were composed in his senior years. Shapmochan (1931), Tasher Desh (1933), Chitrangada (1936), Chandalika (1938), and Shyama (1939) all featured songs supported by dance from beginning to end, with the first two incorporating spoken words as well. Shapmochan drew inspiration from the Buddhist Kush Jataka, combining the rhythmic variation of Kathakali and Manipuri dance with group dance.

Tasher Desh, a reflection on a fossilized society, initially had French influences but later incorporated group dances based on Indian folk forms and solo dances from Manipuri, Kathakali, and Kandyan repertoires. Chitrangada drew from Manipuri and traditional Japanese styles, led by Miki, one of Tagore’s students, while Shyama utilized Bharatnatyam for Bajrasen, Manipuri for Shyama, Kathak for Uttiya, Kandyan dance for Kotal, and Kathakali for Prahari. Tagore’s dance form mainly emphasized classical nritya in group dances, often without abhinaya.

In these group dances, elements from the Manipuri approach of mandala and saari (linear) were combined with choreography from Western ballet, both classical and modern. Over-arching physical gestures, prevalent in other dance forms, were avoided in Tagore’s dances, and there was a preference for fluidity in all compositions.

Rhapsody of song and dance

Some of Rabindranath Tagore’s plays, such as Valmiki Pratibha (1881), Kal Mrigaya (1882), Mayar Khela, and Shaap-mochan (1931), are staged as dance-dramas, but they are, in fact, ‘Geeti Natya’ (song-dramas), where the stories are conveyed through specially written songs. As previously mentioned, these plays by Tagore feature songs and choreography, including Tasher Desh, Raktakarabi, Rituranga, and Prokritir Protoso. He often blended different types and genres of music, including the folk Baul style of Bengal and Western music.

In a similar manner, he integrated various dance forms, such as folk, pure classical Manipuri, and Kandyan dance from Sri Lanka. His work had a global character, embodying inclusiveness and the concept of ‘Vasudhaiva kutumbakam,’ which translates to ‘the whole world is a family’. The evolution of Rabindra-nritya incorporated influences from Manipuri initially, and later, Kathakali and Mohiniyattam from Kerala were added. Tagore’s extensive travels all over India and abroad exposed him to Sri Lankan/Ceylonese (Kandyan), Javanese (Serimpi), and Bali (Legong) dances, which were also integrated into Tagore’s dance initiatives.

Additionally, folk dances like Garba and Baul were incorporated into his dances. Tagore’s style did not emphasize overarching physical gestures and tended to avoid an overuse of mudra—whether in the eyes, fingers, or limbs. Over-dressing and over-ornamentation were also discarded from his dance form. He favoured fluidity in all his compositions. Mandrakanta Bose, a writer and professor with a doctorate from Oxford in Sanskrit textual studies in the classical performing arts of India, describes Rabindra-nritya as the first ‘modern dance’ of India. However, despite its creative impulse and flexibility, Rabindra-nritya has not gained acceptance in India beyond the Bengali cultural domain, largely due to a lack of formal rigour and codification.

Back to the future

An essential figure in nurturing and conserving Rabindra-nritya is Guru Valmiki Banerjee, the founder director of both Delhi Ballet Group (1954) and Rabindranatyam Training & Research Centre in Kolkata. He dedicated himself to researching and promoting Rabindra-nritya. His efforts led to the recognition of Rabindra-natyam as a new ‘Indian Classical Dance’ by the Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India, and senior scholarships were introduced for Rabindranatyam.

Guru Valmiki Banerjee received an honorary doctorate on research of the original form of Rabindranatyam as created by Rabindranath. Other esteemed dance gurus who also received this recognition include Prof. Gayatri Chatterjee, Guru Thankomani Kutty, and Prof. Mahua Mukherjee. Guru Valmiki delved into the works and writings of several individuals, including Pratima Tagore, Abanindranath, Nandalal Basu, Sreemati Hathising Tagore, Amita Sen, Shantidev Ghosh, Sukriti Chakravorty, Rama Chakravorty, Sahana Devi, Jyostna Banerjee, Madam Levy, Alain Danielou, Krishna Kripalani, and Gurusaday Dutta I.C.S., the founder of the Folk Dances Federation of India in 1933.

These sources helped him gain insight into Rabindra-nritya. Additionally, he received support from various organizations and individuals who believed in his work. Despite Guru Valmiki Banerjee’s passing in June 2023, other scholars, including Dr. Shruti Bandopadhyay, continue to study and promote this dance form. Dr. Shruti Bandopadhyay’s book “Rabindranritya: The Dance Idiom Created by Tagore” (2019) delves into Rabindra-nritya and its history. She highlights that scholars and intellectuals began terming the dance introduced by Rabindranath as Rabindra-Nritya from 1936.

Books in Bengali on Rabindranath Tagore’s dance form, such as “Rabindranritya” by Amartya Mukhopadhyay (2019), “Prashnottari” by Nikhil Pal (2020), and “Rabindra Nrityanatya Sekal Theke Ekal” by Indrani Sen (2021), have been well received. These works, along with institutes teaching Rabindra-nritya and performances in West Bengal, Tripura, and other cities in India, as well as Bangladesh and among Bengali diaspora abroad, demonstrate that Rabindra-nritya remains alive in theory and practice.