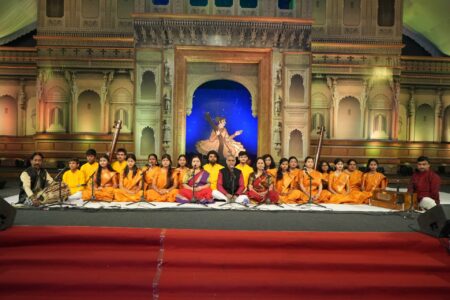

Indiranagar Sangeetha Sabha in Bengaluru is all set to feature ‘Rajamarga’ a unique concert by vocalist Chitra Srikrishna who will bring some gems of Maharaja composers from across South India on September 23.

When Chitra Srikrishna, the Carnatic vocalist known for her innovative thematic presentations, informed me that her next performance in Bengaluru would be ‘Rajamarga,’ exploring the rare kritis of extraordinary royal composers from different eras in South India, I took note of it. Given the in-depth research this subject demands, it’s not just their imaginative abilities that stand out, but also the compositional talent of these selected Maharajas—Swathi Tirunal, Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar, Kumara Ettendra, Shahaji 1, and Kulasekhara Alvar—who have enriched the Carnatic genre in unparalleled ways. Each dimension of their musical knowledge contributes to its vast repertoire.

Chitra has chosen masterpieces from these five royal vaggeyakaras to showcase the distinct features they brought to Carnatic music. She says, ‘As musicians, we need to constantly innovate—whether with well-known songs or those that have never been heard. I believe that as artists, we should strive to “make the strange familiar and the familiar strange.”‘ Chitra, based in Bengaluru, began learning music at the age of five in Hyderabad. She later studied commerce at Sydenham College, Mumbai, and completed a technical writing program at San Jose University in the Bay Area, US.

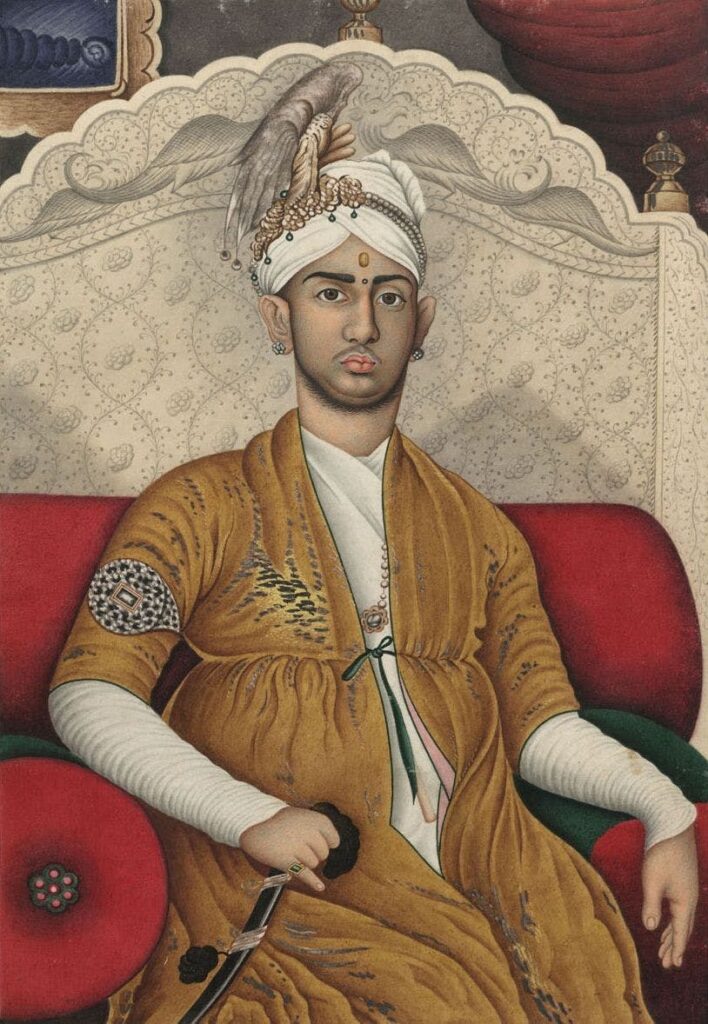

Swathi Tirunal was the Maharaja of the Kingdom of Travancore, Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar was the last of the Mysore royals, Maharaja Kumara Ettendra hailed from the Ettayapuram Royals of Southern Tamil Nadu, Shahaji 1 was the Maratha ruler from Thanjavur, and in Vaishnavite traditions, the bhakti poet Kulasekhara Alvar is described as the King of the Chera Royal family on the western coast of Kerala. Chitra asks, ‘How many are even aware of the Ettayapuram Royal, whose works are so exceptional? How many know that Shahaji’s kritis in Telugu are in praise of Tyagaraja, the deity at the temple in Tiruvarur?’ Chitra immersed herself in the creative works of these Royals to bring this melodic project to life.

Speaking about the Royals whose expressive terminologies and languages gained more posture, individuality, and identity, Chitra explains that while Jayachamaraja Wadiyar chose Sanskrit to compose, Swati Tirunal’s kritis were in Manipravalam, a blend of Sanskrit and Old Malayalam with a distinct appeal. Shahaji’s kritis are exquisite literary verses in Telugu, while Kumara Ettendra’s kritis and Kulasekhara Alvar’s hymns were in Sanskrit.

Chitra Srikrishna spoke to India Art Review about her rare conceptualizations and her other passions.

How did you go about curating the concert ‘Rajamarga’?

My interest in Kulasekara Alvar’s poetic verses, particularly ‘Perumal Thirumozhi’ from the Naalayiru Divya Prabandham, led to a CD release many years ago, for which the religious scholar Velukkudi Krishnan kindly provided an introduction. As I delved into the stories about Chera king Kulasekara, torn between devotion and duty, what struck me was the intense devotion in his verses and his longing to serve at the feet of God, even as an inanimate object.

As a native of Bengaluru, I believe that every classical musician should take pride in learning and singing the songs of Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar, the former Maharaja of Mysore. While preparing for a concert featuring Swati Tirunal’s compositions from the 19th century, which took place at the Pittsburgh temple a few years ago, I was struck by the sheer breadth of his compositions. That’s when the idea of curating a concert featuring the works of these three royal composers first took shape.

Throughout history, rulers of empires, and even localities, have been the primary sponsors of the arts, including poetry, music, and visual arts. Classical music has thrived thanks to the patronage of kings over the years. However, how often do we see such patrons actively participating in the creative process? Did the shared experience of kingship, with its privileges and demands, shape their compositions? Or did the geographical and temporal distance from us result in different perspectives and creative outputs?

Any particular reason for choosing the five mentioned?

Swati Tirunal, Wadiyar, Kulasekara were the first names that came to mind when looking at royal composers. Kumara Ettendra and Shahaji were added to the group. A good friend of mine, the noted musicologist and vocalist, Ashok Subramaniam sent me some kritis of Shahaji when I was discussing the concept of ‘Rajamarga’ with him. He had found this book in a corner of a bookstore specially for music lovers in Chennai. What I noticed was that each royal composer brought something unique to the Carnatic genre —-whether it was the range of Swati Tirunal’s kritis, the erudite lyrics of Jayachamaraja Wadiyar, emotive appeal of Kulasekara’s verses (‘Mukunda Mala’ being his most well known work).

Shahaji I’s kritis appeal in its simplicity and give a glimpse of the lives led by people in his kingdom. For example one of his Operas gives a description of the food items served at a gathering! Kumara Ettendra’s kritis are reminiscent of Dikshitar’s scholarly skills as a composer. While the first two composers (Wadiyar and Swati Tirunal) are well known in the Carnatic circuit the last three are not so well known.

What are the intrinsic features in each that explain the composer in them?

When you take Wadiyar’s compositions (Sanskrit) there is an innate scholarly nature of lyrics and other features that stand out – alliteration of words, his Srividya (upasaka) worship, some of his kritis built in rare raga scales as Durvanki, Shuddha Salavi, Nagadhvani, Bhogavasantham and uncommon talas like Mishra Jhampa and the like.

Swati Tirunal’s prolific contributions span a wide range, encompassing varnams, kritis (including navaratri and kshetra kritis), javalis, padams, Hindustani bhajans, and tillanas. Kulasekara Alvar’s poetic verses, particularly those found in ‘Mukunda Mala,’ are set to music of exquisite beauty and are often performed on concert platforms to extend the reach of his powerful verses to music enthusiasts. In the ‘Perumal Thirumozhi’ one sees the use of allusion and alliteration, poignantly used for his ‘longing descriptive.’

Shahaji I, the Maratha ruler from Thanjavur, is credited to have composed the first opera (‘gheya natakam’) in south Indian music. The credit for reviving this opera of Shahaji’s (Shankara Pallaki Seva Prabandha) stands out for its simplicity in its melody and lyrics goes to the well-known musicologist Prof. Sambhamurthy when it was presented at AIR Chennai.

Kumara Ettendra came from a family of fine arts patrons (royal). His compositions – except for a couple of them – such as Gajavadana (Thodi), and Karunanda Chatura (Neelambari) are not heard in concerts.

Do you still teach music appreciation in universities where guest musicians are invited?

I teach music appreciation at Ahmedabad University. Last semester I taught a new course – “Bhakti & Music – Oral Tradition Radical Change.” In this course, students who are interested in the history and the musical impact of the Bhakti mystics of India explore the roots of the Bhakti movement, and the influence of historical context — political, religious, and cultural – in its development. They learn to appreciate Bhakti poetry and its propagation through multiple musical genres and examine how the mystics across India strove to create social change through the ages that has relevance in modern times.

During the semester we invited Dushyanth Sridhar (katha proponent), Satish Vimal (Kashmiri poet), and Arundhathi Subramaniam (poet) as guest speakers to address students.

Since you sing, curate, teach, research, and write on music, what is it that you would like to share?

I believe we need to appreciate music from different viewpoints – it is much more than a performance art. While classical music is anchored in devotion, other genres of Indian music from folk to bhajans address a wide range of subjects. Songs highlight the beauty of nature, act as markers of festive occasions, and highlight social challenges that still exist in society. When we look at the variety of musical instruments across genres, there is much to discover not just in Indian music but other genres of world music.

Chitra will be accompanied by Charulatha Ramanujam on violin and Ranjani Venkatesh on mridangam in Rajamarga.