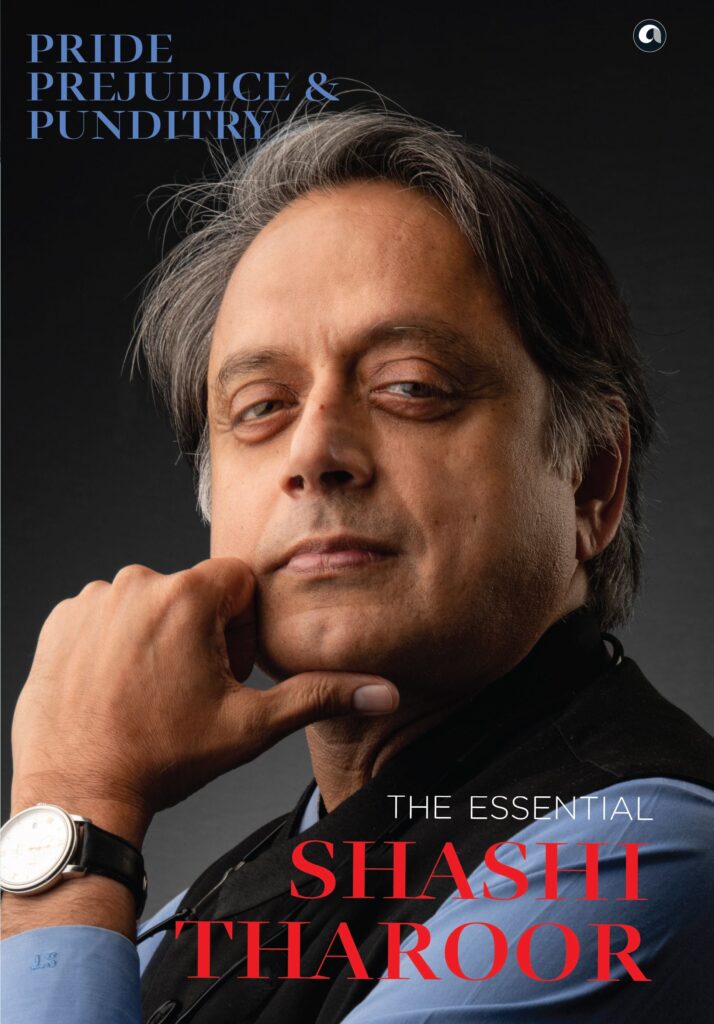

In his book Pride Prejudice and Punditry, Shashi Tharoor writes about how the books he read as a child and the word puzzles he played helped him become the wordsmith he is today.

My journey as a writer began with reading. Growing up in urban India in the late 1950s and 60s, my generation was probably the last that could read without the threat of other distractions. Television did not exist in the Bombay of my boyhood, and Nintendo or PlayStation were not even a gleam in an inventor’s eye; mobile phones and personal computers remained in the realms of fantasy. If your siblings were, as in my case, four and six years younger (and, worse, from a young boy’s point of view, female), there was only one thing to do when you weren’t able to play with your friends. Read. I read copiously, rapidly, and indiscriminately.

It started with my mother reading to me as a tiny toddler, mainly from the Noddy books of Enid Blyton. She jokes that she read so badly I couldn’t wait to snatch the books from her and start reading myself! Which I did from about the age of two. Since then, I have always been a voracious reader.

Chronic asthma often confined me to bed, and in those pre-inhaler, pre-nebuliser days, I would have to just lie propped up, wide awake, struggling to breathe, unable to speak, and without the energy to do anything physically strenuous. Today, that would be a recipe for ‘passive entertainment’ — I picture today’s young asthmatics clicking away at their remotes as a series of images flicker on a screen. Not me. Confined to my bedroom when a lot of my peers and friends were outside playing, and with no TV or other distractions available, books were my escape, my entertainment, and my education. They helped me take my mind off my congested air passages and devote my attention to literary passages instead, and I found so much pleasure in the books piled up by my bedside that I stopped resenting my illnesses.

An abiding memory is of my mother coming into my room around eleven every night and switching off the light. I wasn’t smart enough to think of holding a flashlight under the covers, but sometimes I would wait for my parents to fall asleep in their room, then surreptitiously switch my light on again to finish the book they’d interrupted.

I was a rather rapid reader, with an inconvenient ability to finish a new library book in the car on the way home, and this forced me to become an adventurously eclectic reader. I had no elder siblings whose books I could dip into, so, left to my own devices, I would distract myself with books from my parents’ shelves. These were obviously well beyond my comprehension, for the most part, but I gamely stuck to them and found my vocabulary and interests expanding prodigiously. I did not have the patience to turn to a dictionary each time I encountered a word for the first time, preferring to glean a sense of its meaning from the context, and soon learned that when you have come across the same word in three different places, you understand it fully from the company it keeps. So, words, their meaning, nuances, and usage multiplied in my little brain, even if the full purport of the texts in which they appeared did not necessarily fully dawn on me.

Book Details

Pride Prejudice and Punditry: The Essential Shashi Tharoor

By Shashi Tharoor

Aleph Book Company

600 pages; Rs 999

Publication date: 1 November 2021

The way books can entrance and create entirely new worlds has never ceased to fascinate me. However, the combination of insatiable curiosity, a wide circle of friends whose books I could borrow, and membership in a pair of libraries in addition to the school’s, prompted a madcap idea one year of reading and finishing a different book a day, or 365 books that year. I was thirteen, and with the enthusiasm of a teenager plunged into it with a will, keeping a list as I went along. I hit the magic number before Christmas. But the satisfaction was hollow. The experience taught me, once and for all, that one must read for pleasure and not to a deadline, nor to complete a list or fulfil a quota. The ‘#365BookChallenge’ (in the language of today’s hashtags) was something I vowed never to undertake again. I’ve been appalled at the number of parents and teachers who have cited this episode from my interviews to urge kids to emulate me; I seize every opportunity to make it abundantly clear that I would never recommend it to anyone.

Today, with multiple other demands on my time, reading a single book can stretch over weeks because of the limited opportunities I have available for uninterrupted reading. But that’s far more satisfying than rushing through it just to fulfil an arbitrary target.

Ever since books began to be published, someone or the other has asked the question, ‘what should I read?’ Not ‘what may I read?’ nor ‘what might I enjoy reading?’ but ‘what should I read to improve myself?’ The implication was that familiarity with some books would help a reader to better understand, and so better cope with, the world.

As a result, many looked to their betters for guidance on what they ought to read. For years, newspapers and magazines used to run features in which famous people described what they were reading that week or had read that year—an intellectual equivalent of the fashion pages, a sort of What the Well-Dressed Mind is Wearing. If you want to be as well-informed as that urbane Lord X, ran the unstated assumption, you ought to run out and pick up that volume he’s placed on his bedside table.

But there is a difference between wanting to read a book and wanting a book to read. As a totally individualistic reader myself, when people ask me what they should be reading, my first reaction is always a reflexive ‘anything you want to’. As so many Indians struggle to fill their time, and their minds, during periods like the Covid lockdown, that remains my answer: books. Any book that appeals to you.

To me, books are like the toddy tapper’s hatchet, striking through the rough husk that enshrouds our minds to tap into the exhilaration that ferments within. Whatever you read, whether fiction or non-fiction, biography or murder mystery, comedy or thriller, romcom or chicklit or mythology—books will prove illuminating at times and provocative at others. Read them because you want to, and above all in the hope that they will impart something of the pleasure that the acts of reading and writing have always given me.

More than a century ago, Walter Pater wrote of art as ‘professing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass’. That may be all that reading offers; but it is no modest aspiration.

The love of books brought with it a love of words. And it wasn’t just for their own sake—rather, I was fascinated by the way they can be used to express a sensibility, to convey a style, to persuade and amuse, to communicate all manner of ideas and feelings. Books—both novels and non-fiction—proved to be the best pathway to the wonderful world of language, and language the key to unlock the wonderful worlds captive inside books.

My father, Chandran Tharoor, was an immense influence on my life. He was a teacher, guide, research adviser, imparter of values, my source of faith, energy, and self-belief. My enthusiastic approaches to life and learning are inherited from him; so is my work ethic—and my love for words. He was a word-game addict, from Scrabble to Boggle and acrostics in newspapers, and would make up games with my sisters and me, seeing how many words with four letters or more we could make up from the letters in a nine-or-ten letter word. Another one we played on long car journeys was when one passenger had to imagine a five-letter word, and the others guessed at it for twenty attempts by trying out five-letter words and being told only how many letters matched. This great love of words and language, and the inventive ways my father put it to practice, inevitably rubbed off on his eldest child.

But it was never just words for their own sake. My father instilled in me the conviction that words are what shape ideas and reflect thought, and the more words you know, the more precisely and effectively you are able to express your thoughts and ideas. He roped me in to speaking words out loud as well, pushing me into my school’s elocution and debate contests, even when it initially meant writing my speeches himself. And he was, for years, the first reader of my articles, as well as the first audience for my declamations. Either way, words, whether uttered or chiselled in print, became the valued vehicles for what I wanted to say to the world.

(Excerpted with permission from Aleph Book Company from Pride, Prejudice and Punditry)

Write to us at [email protected]