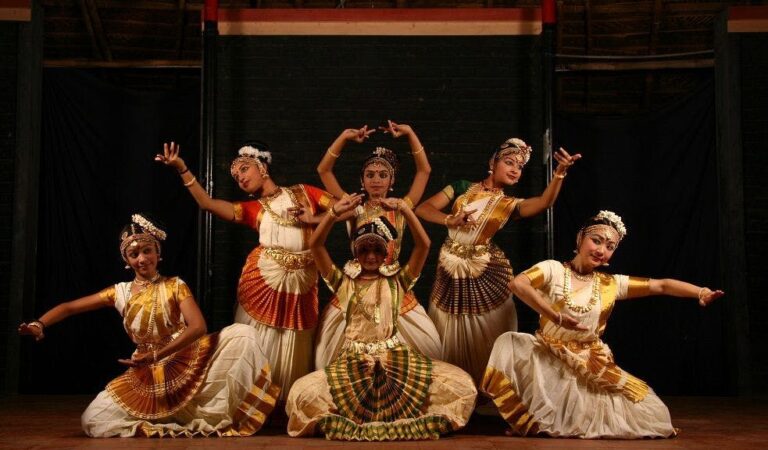

The manuals for several Kerala art forms like Koodiyāṭṭaṁ and Nangiārkūttụ are said to have been formed during the age of the Kulasekharas, who followed the Chera dynasty in Kerala. The current day Mohiniyattam can be considered a dance form in the lasya style which imbibed the core principles of many ancient dance forms of Chera influence

The Chēras together with Pallavas and Pandyas were the three major dynasties that ruled parts of South India that currently belong to the States of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The Chēra dynasty controlled western Tamil Nadu and central Kerala during the medieval period.

The birth of the Malayalam language

During the 8th to 9th century, the present-day central Kerala separated from the Chēra kingdom and became the Chēra Perumal kingdom. It is believed that the title Kulaseskhara is associated with these Chēra Perumals who succeeded the ancient Chēra dynasty in central Kerala. Scholars associate the Alwar saint Kulasekhara Alwar with these Chēra Perumals. However, historians point out that this second Chēra dynasty could not have been a strong absolute monarchy. Instead, the kings, with their base in Makodayapuram (Kodungalloor) had namesake sovereignty over a fragmented array of local chieftains, with the power largely vested in a Brahmin oligarchy. This period is believed to have contributed to the religious and cultural spheres of medieval Kerala. Most notably the language of Malayalam started to diverge from Tamil. The Kulasekharas are believed to have started using the Vattezhuthu script that is found in several inscriptions across Kerala. It is also believed that Kulasekhara Varma reformed the Sanskrit theatre of Kerala, Koodiyattam, by restructuring the format of the plays and introduced the local language for the Vidushaka.

Evolution of Kerala dance forms

During this period, performing arts received great patronage under the Kerala Perumal. Dancers were brought to Kerala from Tamil Nadu during the time of Kulasekhara Perumal. It could be assumed that during this period the Dēvadāsis also might have made their entry into Kerala, which also had a long history of various women’s dance forms.

The descendants of some of these families who were brought to the Kodungallur temple by the Chēra kings still retain their relationship with the temple and enjoy several rights. In the Kodungallur temple, women from these families wield the right to carry the lamps in the temple procession. Before the entry of these Dēvadāsis, many other distinct forms of dances existed in Kerala.

The dancers of the Chēra Kingdom mostly followed the style of enacting the stories of Gods through dance, similar to Nangiārkūttụ, Kuṟattiyāṭṭaṁ etc. It is believed that acting manuals for Koodiyāṭṭaṁ and Nangiārkūttụ were formed during the time of Kulasekhara Perumal. The legends surrounding Nangiārkūttụ support this premise. The main story of Nangiārkūttụ is Śrīkriṣhṇa Charitaṁ, taken from Bhāgavataṁ, 10th skanda. References in Chilappatikāraṁ denote that the same story was exclusively performed by groups of women dancers.

Kulasekhara to Swathitirunnal

In Chilappatikāraṁ, we find many more ancient Dravidian traditions as well. We have already seen that since the Saṁghaṁ age several dance forms like the Kuṭaikūttụ and Tuṭikūttụ of Subramanya Swāmy, Malkūttụ of Srikrishna, Koṭukoṭṭyattam of Sri Parameswara, group dances like Thiruvāthirakkaḷi and dance forms exemplifying kings and heroes were in vogue in Kerala. Even today, many aspects in these references could be traced to some of the dance forms of women of Kerala. For example, Patiṯṯupattụ, a particular women’s dance form similar to Nangiārkūttụ, is performed in the light of an oil lamp accompanied by the percussion instrument called Muḻa. This could be an allusion to Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ since the term Muḻa is also used for Maddaḷaṁ (Tabor) which could be played on both sides. In Thiruvāthirakkaḷi, Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ and Kuṟattiyāṭṭaṁ, a lighted lamp is kept in the centre of a stage for the performance. With the passage of centuries, many changes might have appeared. Remarkably, a lāsya dance style which had imbibed many core principles of these ancient dance forms still remains in Kerala.

Works of the Saṁghaṁ era mention dancers denoted as actresses. Chilappatikāraṁ elucidates that these dancers performed both dance and drama, a reference found in Dhanañjayaṁ, a play written by Kulasekhara Perumal. The king also wanted some of these dancers to perform in his drama troupe. Legends in oral tradition allude that those Naṅṅas who joined the drama troupe, later on, came to be known as Nangiārammas.

Rama Varma Kulasekhara who ruled between the later 11th and early 12th CE was the last of the dynasty. He is believed to have lost a fierce war with the Cholas in which the headquarters of the Kulasekharas, Mahodayapuram, was burnt by the Cholas. Rama Varma fled to Venad, the present-day Kollam, and fought the Cholas from there. It was the end of the Kulasekhara kingdom based in Kodungallur. The Venad kingdom is said to have formed the basis of the later Travancore kingdom, that was formed in the 1700s. Irrespective of the lineage, Travancore kingdom seems to have inherited the patronage of arts from the Kulasekharas. It is well known that Swati Thirunal of the Travancore kingdom was instrumental in the revival of Mohiniyattam in the early 19th century.

Read Part 8

(Assisted by Sreekanth Janardanan)