Preserving Mohiniyattam’s gestures and dance movements in the form of notations.

Recording information and important milestones in any art form is as crucial as practising the art. While many artists focus on practice, performance and teaching, very few dedicate time to record their contribution. This is especially important in art forms that have very few written historical documents or official archives. Mohiniyattam, as we have learnt in the past few articles, suffered from disrepute around the early 1900s and later legends such as Vallathol Narayana Menon, who set up Kerala Kalamandalam dedicated a lifetime to revive the art forms.

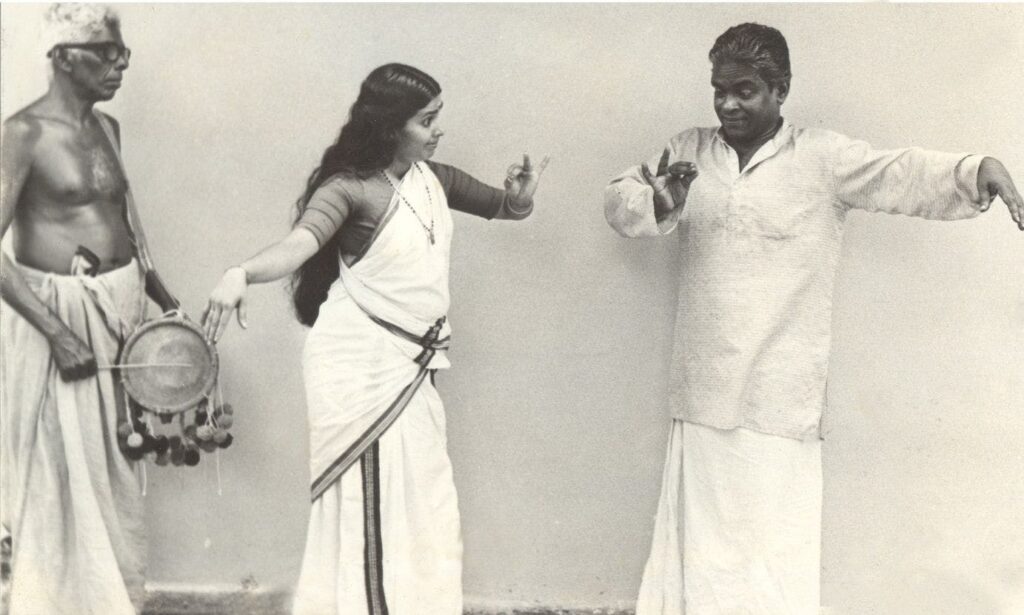

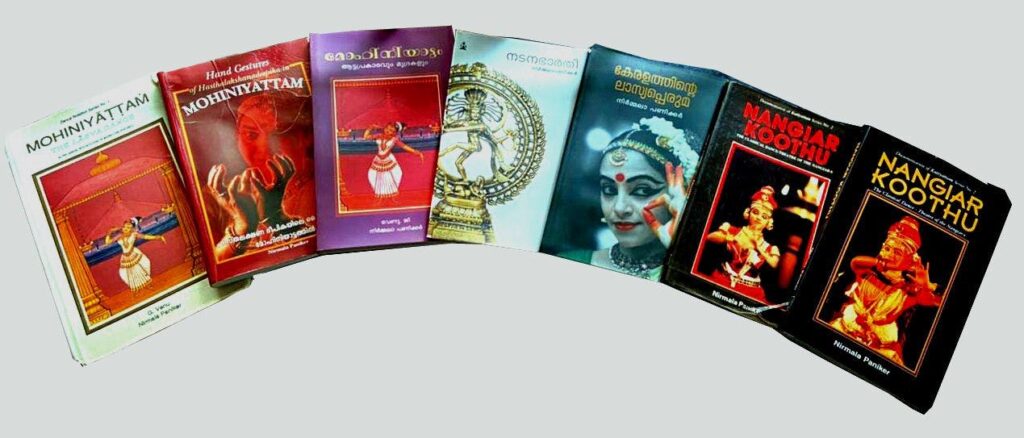

Keeping in league with reviving, nurturing Mohiniyattam, we also undertook writing books on Mohiniyattam. One of the earliest works I took on for a book on Mohiniyattam together with G. Venu was notating the Mudras and important Mohiniyattam choreographies using a unique notation system, initially developed by Venu for notating Kathakali Mudras.

Lost in translation

Oral tradition has been the accepted medium for transmitting the modes and techniques of Indian dance from generation to generation; and from teacher to student. By its very nature, oral tradition is open to alteration, misinterpretation and even omission. To a certain extent, works such as the Natyasastra and Abhinaya Darpana served as records that codified and set down dance practices current at the time when the records were compiled. However, purely verbal descriptions are never able to transmit in its totality and exactness of body movements. It can never capture the essence of the movement: its creation in time and space.

Throughout India, even from the very ancient times, performing artists of each locality have received artistic representation in murals, wood carving and sculpture. The ancient rock-paintings of Bhimbeteka and Mirzapur, and the sculptural marvels in the Nataraja temple at Chidambaram, which elucidate the Karanas described in the Natyasastra, are examples worthy of special mention. However, even these records in painting and sculpture, have failed to do justice to the synthetic aspects of dance movements, which take place in space and time.

Setting up the right practices

The attempts to record movement through time and in space led to the development of notation systems (recording movement by means of symbols on paper) in the West. This delineation of dance movements began with the upsurge in western cultural interest in dance as early as the 15th Century with the earliest known dance notation system available from two manuscripts in Spain. One of the prominent notations systems in the West in the 20th Century was developed by Rudolf Von Laban and was called as Labanotation. Kapila Vatsyayan, one of the eminent theoretical exponents of Indian-dance forms, has used this notation system to record some of the techniques of Indian dance.

Marianne Balchine has attempted to record through the medium of ‘Banesh Movement Notation’ initiated by Rudolf and Joan Banesh, some techniques of Indian dance, especially those relating to Bharatanatyam. During Venu’s London visits in 1980 and 1982, he had occasions to meet with and conduct a detailed discussion with Marianne Balchin. It is not known whether there have been any other serious attempts to record Indian dance forms in dance notation.

The birth of a special system

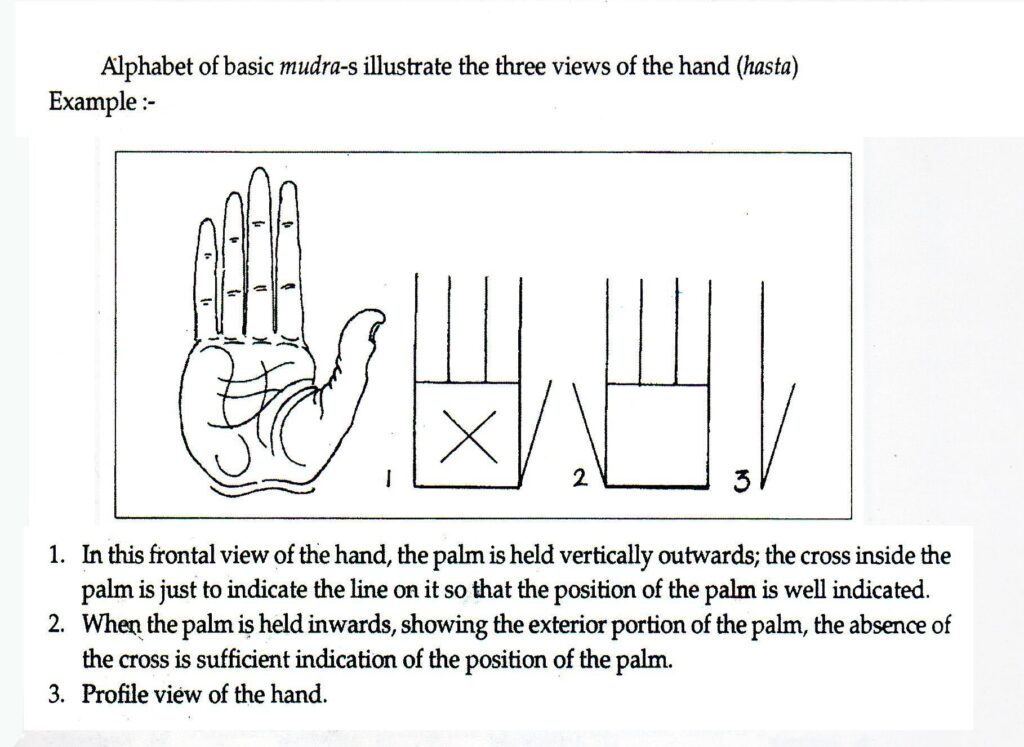

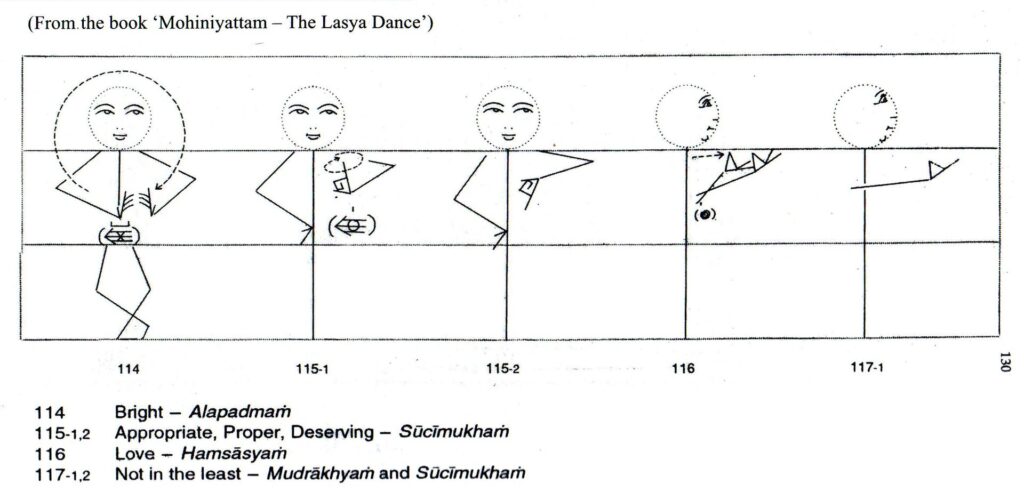

As with the case of Indian music, Indian dance patterns have a separate identity from western ones. The diverse Indian dance forms not only involve a large kinetic vocabulary of the micro-movements of the hands and the different parts of the face, complicated footwork, but also stylized movements of parts and organs from head to foot. To record all these, a special notation system was needed. Venu undertook extensive research to develop a notation system for documenting the variations of gestures, mudras or the hastas of Kathakali – the form in which he initially trained.

Just like the way alphabets are made of basic symbols, Venu developed a collection of symbols for basic hand gestures. He approached renowned Kathakali exponents and collected several mudras (including some rare ones) and documented them. In 1968, Venu also published a booklet Alphabets of Gestures in Kathakali.

For the first time in the history of dance notation, an international exhibition in 1986, under the label ‘Four Hundred Years of Dance Notations’ was organized in Grolier Club of New York and the Harvard College library. The exhibition, which grabbed the attention of the dance enthusiasts, displayed 55 original notation systems from the 16th Century up to the present. Venu’s notation system was chosen to represent at the exhibition from the Asian countries.

Applying the new system

The positive response to the book from professional dancers and students from across Kerala and other parts of the world were encouraging. We decided to extend the work by using the same approach to notate dance forms including Mohiniyattam. In 1984, Venu and I jointly published a book on Mohiniyattam —Mohiniyattam: Attaprakaram with Notations of Mudras and Postures — in which we used the previously established notation system to document the hastas and movements of Mohiniyattam for the first time.

In 2007, I wrote another book, Hand Gestures of Hasthalakshanadipika in Mohiniyattam and used these notations to elicit the Mohniyattam mudras. The notation system that Venu developed and all activities of Natanakairali in reviving declining art forms of Kerala significantly helped me in my Mohiniyattam research. Through numerous research projects and workshops organised by Natanakairali, I had the opportunity to interact with artists and scholars from the different disciplines that helped me develop a holistic view in approaching dance and the Abhinaya traditions of Kerala.

(Assisted by Sreekanth Janardhanan)

Click here or more on the series

Write to us at [email protected]