Marking the death anniversary of the saint-composer , the acclaimed Thyagaraja Aradhana is being held today at Thiruvayyaru. From the bhakti poets of the eighth century to the trinity that includes Thyagaraja, Indian music advanced through devotion. This was induced by ragas that are unique to the subcontinent’s music system.

All the ancient books right from Natyasastra, have looked upon music as a spiritual pursuit. Sangita Ratnakara defines both marga and deshi sangeeta. Marga sangeeta, it says, is that which is margita i.e. the way that was shown by Brahma and other divine beings and which was put into use by Bharata and other musicians; which when performed can lead to prosperity and bliss.

The very word nadopasana shows that it was a form of yoga (union) between the human and the divine. Sangita Darpana says, “One who knows the principles of playing the veena, one who is an expert in sruti, jaati etc and has a mastery of tala attains moksha without any effort”. Externally observed, music comprises raga, tala, sahitya and so on. It is a stream of sound having a particular effect.

In Indian tradition, this effect is identical with the experience of the mystic. The seers realised that nada has the power to attract the mind and absorb it. Thus nada-yoga came to be seen as an effective and safe means of self-realisation or self-awareness – a vehicle to attain a level of consciousness beyond emotions marked by “calm of mind, all passions spent” – a pathway to peace that surpasses all understanding.

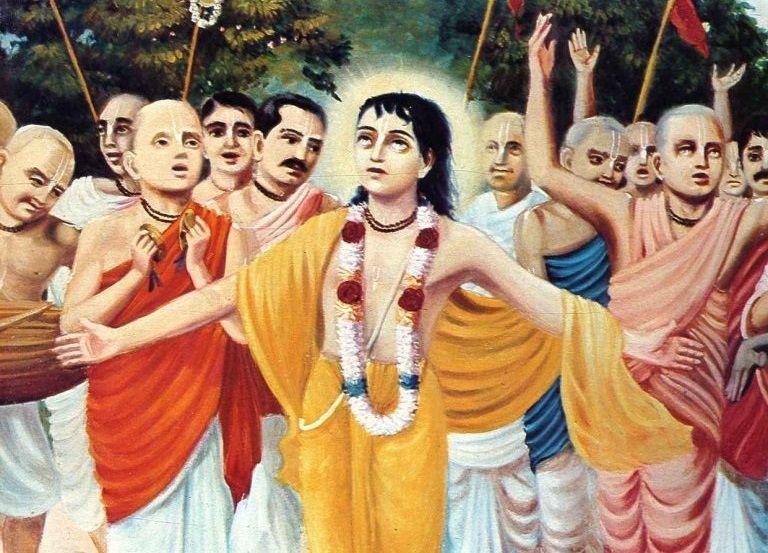

Bhakti poets and bhajans

It was therefore inevitable that those who expressed bhakti through poetry or those who recited such poetry to voice their devotion would combine poetry with the sound of music. The result, therefore, was fabulous. India abounds in devotional music, perhaps to an extent no other culture does.

One can see how the prodigious output of numerous bhakti poets and musicians has been instrumental in the shaping of our music. Gnanasambandar, Thirumangai Alwar of the eighth and ninth century, Jayadeva, Namdeva and Jnaneshwar, of 13th and 14 centuries, Guru Nanak, Purandaradasa, Annamacharya of 15th and 16th centuries, Tulasidas, Surdas, Meera of 16th and 17th centuries, Narayanatheertha, Guru Govinda Singh, Bhadrachala Ramadas of 17th and 18th centuries, to mention a few.

The bhajan music that emerged during this period enjoyed enough clout on the compositions of the vaggeyakars(composers) the most prominent among them being the trinity (Thyagaraja, Muthuswamy Dikshitar and Syama Shastri) itself. And of course in Kerala, Maharaja Swathi Thirunnal . Of the different aids to bhakti namely sravanam, vandanam, smaranam, sevanam and kirtanam, the vaggeyakars dwelt on kirtanam, the hymns sung in praise of the deity of their choice.

Thyagaraja: The epitome of devotion

Of the thousands of Thyagaraja’s compositions, only very few have been salvaged. All of them are striking paradigms of his unstinted devotion to Rama as well as music. In ‘Moskshamu galada’, set to Saramathi raga, he expresses his doubt whether one ignorant of sangeeta gnana can ever get moksha. Again in the Dhanyasi composition, ‘Sangeeta gnanamu bhakti vina’, he argues that sangeeta gnana is a blending of bhakti and sanmarga. An attempt to analyse the compositions of Muthuswamy Dikshitar and Shyama Shastri can also reveal bhakti as the leitmotif. Needless to mention those of Swathi Thirunnal who had called himself as Padmanabhadasa. His work Bhakti Manjari contains 1000 slokas in praise of Padmanabha.

Raga and rasa is an interesting topic in musicology. But the association of rasa with raga occurs only in applied music and not in art music. The function of art music is to provide aesthetic enjoyment, which is independent of any rasa. By listening to this type of music we derive genuine pleasure without, at the same time, receiving any suggestion of a particular feeling. We feel lifted to sublime heights. It is this experience that has been described as sangeetananda. And this is beyond description in any language too. You may call it ecstasy, bliss, visranthi or whatever.

Raga: The identity

It is worthwhile at this juncture to know how Indian music has been described as irrational and intuitive as against its western counterpart that is rational and discursive. While the latter appeals to the intellect, the former appeals to our psyche. The communication in art music takes place at a psychic level, which is well above the intellectual level. Evolution of this esoteric system of music would have been impossible without the motivating spirit of bhakti.

The demarcating character of Indian music, namely bhakti is both its strength and weakness. The strength emanates from the ingenious technique of raga with the use of the 22 microtones that elevates melody to sublime levels, insuperable to any other system of music in the world. At the same time, it can’t entail any motif that warrants thematic descriptions as possible in western music.

But these are days when such attempts are being made for which the influence of western music and its techniques are instrumental. Even in such attempts for fusion, we can see how a raga retains its identity and creates an ambience of spirituality for the short duration of its occurrence. The style of all art is a product of social consciousness, goes the axiom. But one wonders how far it is true in the case of the Indian art music, the intrinsic factor of which is nothing but bhakti.

Read Part 1 here